The 21st century has revolutionized the way energy is produced, stored, and utilized, with battery innovation playing a key role. This insight provides an introductory overview of the geopolitics surrounding battery technology and emerging trends.

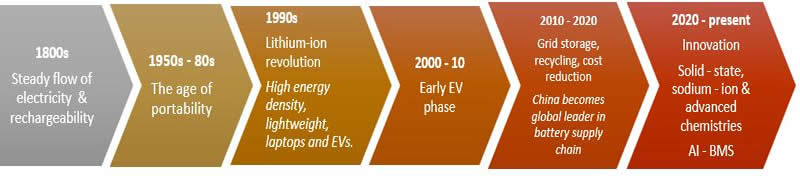

Batteries have come a long way since their inception in the 1800s (Figure. 1), now powering nearly every aspect of modern life, from smart gadgets and electric vehicles (EVs) to large-scale grid storage for renewable energy integration. Battery dependence will only intensify as the world shifts towards decarbonisation. In modern military operations, they support communications gear, night-vision devices, unmanned ground and aerial vehicles, submarines, wearable power sources for soldiers, and backup energy systems for forward bases and field hospitals. This widespread use underscores their dual and indispensable role.

Figure 1

Source: Compiled by Author

Today, the emphasis has shifted to miniaturisation and sustainability. Smaller, lighter batteries with higher energy density enable longer-lasting drones, portable military gear, and compact electronics. These advancements allow devices to run longer without increasing in size, making energy storage more practical and versatile. While lithium-ion (Li-on) batteries remain dominant, growing concerns about safety, resource scarcity, and environmental impact are accelerating the shift toward other chemistries that promise greater efficiency, safety, and longevity.

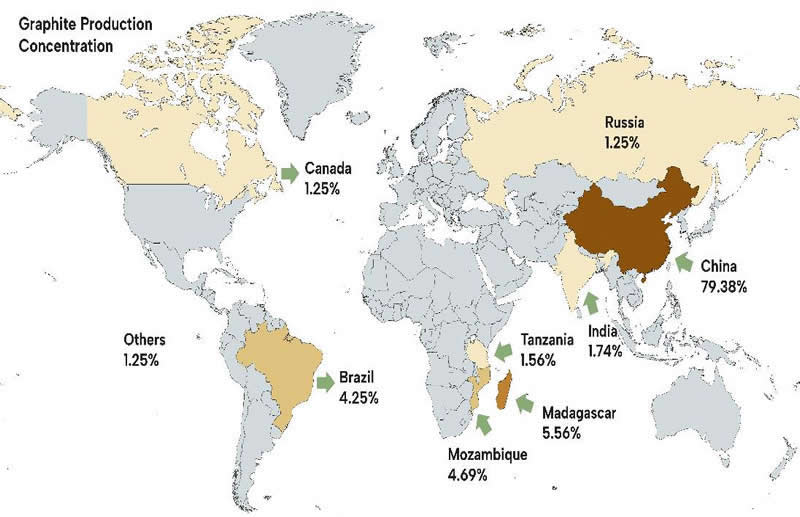

Figure 2

Source: Lithium Harvest

Academics increasingly describe Li-on batteries as geopolitical. Firstly, battery raw materials such as lithium and graphite are unevenly distributed (Figure. 2,3). Second, the battery supply chain is a highly globalized and fragmented process involving extraction, refining, manufacturing, and recycling across different geographies.

For instance, while the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) holds approximately 52% of global cobalt reserves and supplies over 70% of recent cobalt mine output, around 75% of global cobalt refining is done in China. From 2026, the DRC’s 96,600-ton cobalt export quota is expected to tighten supply and drive price volatility, reinforcing China’s refining leverage.

Figure 3

Source: Statista

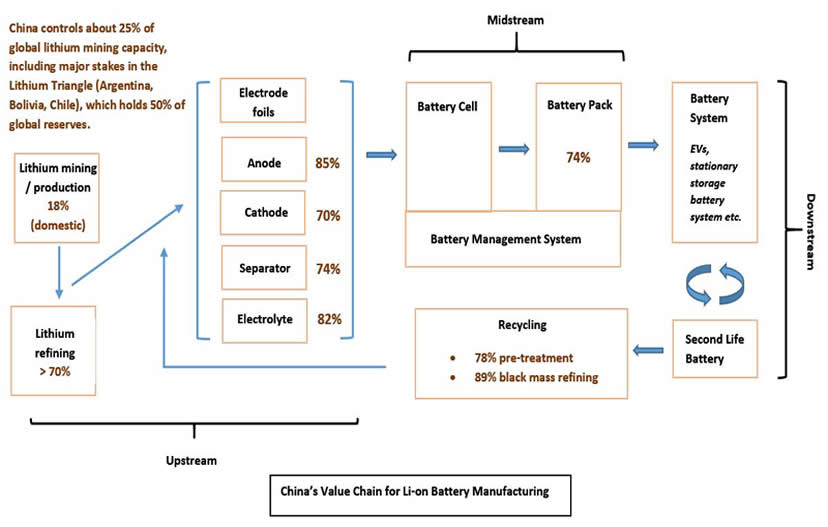

Similarly, Australia dominates lithium production, but China leads in refining, with a 70% market share. Such structural dependencies within battery supply chains create a division of labour that bolsters the strategic value of refining and manufacturing capacities.

Due to these reasons, states are actively shaping battery politics through subsidies, trade barriers, and investments in Research and Development (R&D). This enables them to leverage battery markets for strategic advantage, as seen in China’s 2023 export permits on graphite which tightened global supply and created macro-risks for EV and high-tech industries.

Consequently, China has emerged as the undisputed leader in the Li-on battery market. It controls over 75% of global Li-on battery production capacity, dominating most stages of the supply chain through state-supported vertical integration (Figure. 4). This includes upstream extraction and processing of critical minerals to midstream manufacturing of battery cells, modules, and packs, and finally to downstream integration in electric vehicles and energy storage systems, followed by end-of-life handling via recycling and second-life repurposing. Leading firms such as CATL, BYD, EVE Energy, and Tianqi Lithium are prominent players.

Figure 4

Source: Adapted from Xieshu Wang’s brief with data compiled by author from UN Comtrade and other sources.

From 2001, China made EVs and their batteries a priority in its Five-Year Plan, prompted by the assumption that it could not compete in the internal combustion engine. Moreover, it has strategically created a battery overcapacity of up to 400% to drive down global prices, undermining the competitiveness of foreign firms and cementing its dominance. This has prompted the U.S. and its allies to view battery imports from China as a key vulnerability, given growing concerns over technological dependency and the potential weaponisation of supply chains.

Companies like LG Energy Solution, Panasonic, and Tesla are expanding capacity and investing in domestic supply chains, supported by the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and EU Battery Directive; U.S. battery manufacturing investment reached $40.9 Billion (Q2 2023–Q2 2024), while experts note that announced EV battery capacity already exceeds projected demand, reinforcing concerns about overcapacity and potential price competition. Firms like CATL are also preparing commercial sodium-ion (Na-ion) rollouts (2025–26), signaling that next-generation chemistries are moving from lab to market.

With significant R&D investments already poured into the market and China’s dominance, the Li-on battery market provides little wiggle room for disruptive innovation or competitive entry, and suggests that perhaps the battery has reached a point of technological maturity. However, the next generation of solid-state batteries (SSB), lithium-metal, and Na-ion chemistries provides an avenue to the U.S. and its allies to outpace China, especially as they do not use graphite, which China significantly controls.

Their strategic value is reflected in the growing investments by states: the SSB market is projected to grow from $119 million in 2025 to over $1.3 billion by 2032, with Asia-Pacific already holding 44% shares. China, in particular, has committed over $830 million in 2024 to support companies like CATL, BYD, and Geely in advancing SSB technology. Meanwhile, the U.S., Japan, and South Korea are racing to commercialize SSBs by 2030, with firms like Toyota, Quantum Scape, and Samsung making billion-dollar commitments in R&D. This intensifying competition underscores the next battery race that will shape future energy and security architectures.

Battery recycling, valued at $26.9 billion in 2024 and projected to reach $77.1 billion by 2034, offers a circular pathway to reduce raw material reliance and environmental impact. Global capacity exceeded 300 gigawatt-hour per year (GWh/year) in 2023, over 80% in China, while Europe and the U.S. held under 2% each. If all announced projects proceed, global recycling capacity could reach 1,500 GWh by 2030, with 70% in China and 10% each in Europe and the U.S.

Pakistan currently lacks a dedicated battery policy, regulatory framework, or industrial base beyond lead-acid production. Small private firms are driving existing progress in Li-on assembly; Na-ion adoption has not yet begun commercially, though the government plans to collaborate with Chinese partners for development. Pakistan needs a framework that corrects tariff distortions, which currently penalize local assemblers, sets up national testing and certification labs aligned with UN and International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) standards, and enforces Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) rules for safe collection, recycling, and traceability of batteries.

Rather than pursuing upstream cell manufacturing, which is commercially unviable given Li-on’s continuous price decline, China’s economies of scale, and its overwhelming control of the supply chain, Pakistan’s best entry point is quality-controlled pack and Battery Management System (BMS) assembly. This offers value addition at relatively low capital cost, helps reduce the import bill, and may even allow Pakistan to leverage rising tariffs on Chinese batteries abroad to explore export opportunities.

Anchoring demand through EVs and solar can provide scale, as the electricity surplus and large two- and three-wheeler markets already create momentum for electrification. Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) strengthen this ecosystem by enabling peak-load management and providing backup power for commercial and industrial users. Telecom backup systems, which are already shifting from lead-acid to newer chemistries, also provide a near-term demand anchor.

A dual-chemistry pathway should guide this phased strategy. Li-ion should remain the priority for high-performance applications such as EVs and large-scale solar storage, with imports already rising from 1.25 GWh in 2024 to a projected 8.75 GWh by 2030. In parallel, Pakistan can prepare for Na-ion, a lithium- and cobalt-free alternative that is being scaled in China and could suit moderate-use applications. Over time, phased investments in assembly, recycling, and university-led research can position Pakistan to participate strategically in both chemistries while avoiding the sunk costs of competing in cell manufacturing.

In short, the global battery market is shifting towards new chemistries and circular economies, with states racing to secure dominant positions. For Pakistan, a phased policy nurtured by domestic demand and joint midstream ventures with China would provide a realistic pathway to create industrial opportunities and capture value within the evolving battery landscape.