The Arctic covers an area of 14.5 million square kilometers centered on the North Pole. It comprises the Arctic Ocean, parts of Russia, Canada, the US, Iceland, Greenland, Finland, Sweden, and Norway. While the Arctic Ocean, particularly its central high seas beyond national Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), is considered a global common governed under UNCLOS, the broader Arctic region, which includes the land and maritime zones of the eight Arctic nations, is not formally designated as a global common.

Figure 1

Source: Shutterstock

Nevertheless, the vast untapped natural resources, emerging sea routes, and the region's strategic importance have attracted aggressive posturing from global powers. This insight underscores the growing geopolitical rivalry in the Arctic region, fueled by accelerating ice melt and the strategic interests of major powers.

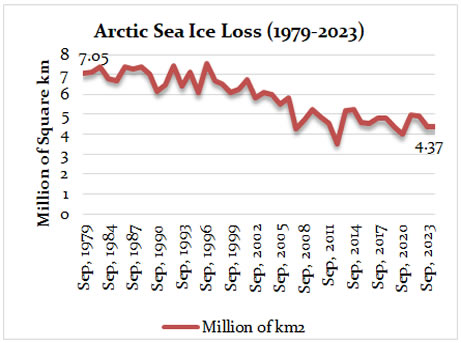

The Arctic sea ice loss (Figure 2) shows an alarming decline. This decrease over the years highlights the severe impact of global warming. Although yearly fluctuations occur, the overall trend confirms an accelerating ice loss. This signals broader climate instability and increases geopolitical interest in the region’s newly accessible routes and resources.

Figure 2

Source: Self-Visualized by the Author from Various Sources

For centuries, ships have traveled from East Asia to Europe via the Suez Canal, covering approximately 21,000 kilometers and taking about 48 days. Due to global warming and melting ice, a new shipping route, particularly the Northern Sea Route (NSR), is emerging. This will significantly reduce the distance of sea shipping by 12,800 km and the duration by 10 to 15 days (Figure 3), resulting in faster delivery of goods, lower fuel costs, increased revenue, and greater profits.

It will particularly benefit the Arctic countries, China, and the European nations in terms of global trade and will potentially stimulate economic development for shipping companies. Controlling this region would enable countries to secure significant influence over international trade flow and attract the interest of both Arctic and non-Arctic states.

Figure 3

Source: The Economist

As Arctic ice melts, it has revealed previously inaccessible reserves of oil, gas, and minerals (Figure 4), presenting opportunities for major powers to pursue their economic interests. This includes resource extraction, particularly from Greenland, which accounts for 148 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, 31.4 billion barrels of oil, and 1.5 million metric tons of rare earth minerals. This represents almost 20% of the world’s available reserves and nearly 10% of global resources. According to the US National Intelligence Council, an estimated $1 trillion worth of minerals and metals will be available in the Arctic, essential for manufacturing semiconductors and batteries. Thus, these resource-driven interests also heighten the geopolitical competition in the polar region.

Figure 4

Source: Self-illustrated, data compiled from the US Geological Survey

Nevertheless, rising tensions among major powers in the Arctic region have triggered increased militarization by both NATO and Russia, strengthened strategic cooperation between Russia and China, and prompted the European Union (EU) to revise and reinforce its regional policies. (Figure 5 highlights Russia’s regional strategic dominance, followed by the US).

Figure 5

Source: Dragonfly

Russia, with 53% of the Arctic coastline, has a powerful icebreaker fleet, a modernized navy, and new hypersonic missiles designed to evade US sensors and defenses. It revitalizes Soviet-era military bases, especially around the Kola Peninsula (most of the peninsula lies in the Arctic Circle), signaling deterrence and strength against the US and its NATO allies.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) initiated the 2024 Arctic strategy, a defense-oriented plan to safeguard the US national interest in the Arctic. According to which, the US plans to boost its Arctic military capabilities, emphasizing stronger monitoring, uncrewed systems, satellites, and allied cooperation. It has also launched an Icebreaker Collaboration Effort (ICE) in 2024, a strategic trilateral initiative of the US, Canada, and Finland to build more icebreakers. While recognizing the strategic value of Greenland, the US has enhanced its presence since 2019 by reopening a consulate in Nuuk, signing MOUs with the Ministry of Greenland, and offering $12.1 million in aid for tourism, mining, and education. Additionally, most recently, President Trump has expressed interest in purchasing the island. This reflects the US’s influence to undermine the strategic presence of Russia and China in the region.

China has incorporated the Arctic into its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), developing a “Polar Silk Road” plan for Arctic shipping and asserting itself as a “near Arctic State.” It has built a large navy and is gradually increasing its Arctic footprint via icebreakers and partnerships with Russia. It also operates four polar research vessels, and in 2023, China invested in the Russian Projects along the NSR and conducted joint naval exercises. Moreover, to expand its influence, it heavily invests in mineral exploration projects, such as Greenland’s Kvanefjeld (a rare earth and uranium mine), which conflicts with US interests.

Meanwhile, the EU's policy in the Arctic region has evolved from an environmental approach (focused on climate change) to a geopolitical and strategic one. However, it seeks to access the critical minerals to reduce its dependency on external suppliers. The EU is facing a dilemma in balancing the demands of US security concerns with those of China’s and Russia’s growing economic interests in the region.

The Arctic Council (1996), a leading intergovernmental forum, is responsible for promoting cooperation among Arctic states and other stakeholders on Arctic issues, including environmental protection and sustainable development. It has eight member states, including the US, Russia, Canada, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, and Finland, with territories within the Arctic Circle. The Council serves as a key platform for addressing the region’s evolving challenges; however, the exclusion of security and military matters from the Council’s mandate, along with its lack of binding authority, has impacted its ability to tackle complex security challenges and shape Arctic geopolitics.

While considering the Arctic Council’s limitations, there is an urgent need for a new international security framework that regulates military activities, ensures peaceful cooperation, and facilitates effective crisis management. However, if the current trends continue, the existing rivalries and major power competition will soon transform the region into a zone of Cold War, where the need to balance security, sovereignty, and sustainability will ultimately shape the future of Arctic geopolitics.

The views expressed in this Insight are of the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect the policy of ISSRA/NDU.