Pakistan’s Hazardous Waste Management Policy defines recycling as the “reclamation and processing of waste in an environmentally sound manner for the originally intended or other purpose(s).” Despite growing interest in recycling and its benefits, the industry remains underutilised in Pakistan. This Insight suggests that, considering the significant economic benefits from the recycling industry, Pakistan’s government must formalise the presently informal, underinvested sector through systemic reforms.

Minimising waste through the recycling process is an essential component of the waste management phenomenon. Having a robust recycling industry is crucial because it diverts trash from environmentally hazardous landfills and ensures materials’ reintegration into a circular production chain. Moreover, by generating new economic activities and reducing costs, it stimulates GDP growth.

The viability of recycling lies in creating sustainability-oriented jobs, saving energy costs of extracting raw materials, reducing imports, and preventing expenditure on tackling pollution by not allowing it to occur. The global recycling industry annually conserves ~850 million metric tons of raw materials by utilising existing waste to manufacture valuable products, besides employing 56 million+ people worldwide.

Waste Sorting in Pakistan

Source: Heinrich Böll Foundation

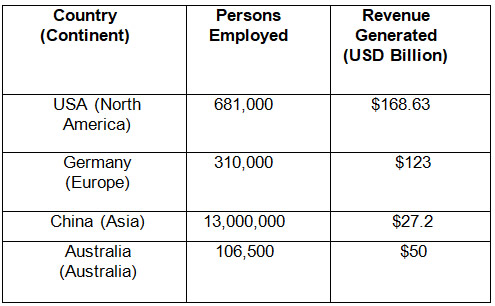

Data from recent years on the jobs and annual revenues approximately accrued from recycling industries across four continents illustrates how measurable economic benefits can be reaped when the sector operates formally:

Table 1: Global Macro-Level Economic Contributions by Recycling Industries

Source: Multiple

Figures in Table 1 demonstrate how Pakistan can similarly boost its economic growth if it patronises its recycling industry.

This can annually generate 337.8 billion PKR ($1.2 billion) in revenue from plastic waste alone, besides creating millions of jobs (exact projection not available).

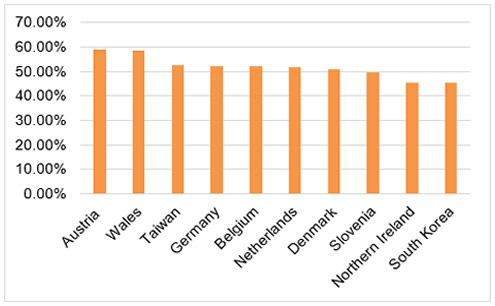

Looking at the big picture, recent global trends in recycling are depicted in Graph 1, based on a Welsh Government-funded report. Predictably, Western and Central European states dominate the world’s top 10 recycling list:

Graph 1: Top Municipal Recycling Rates Globally (Published 2024)

Source: Author’s Compilation

Austria ranks as the world leader in terms of the tons of waste recycled, owing to investments in recycling infrastructure and environmental education. Wales also boasts a heightened recycling profile since its 2010 fixing of recycling targets and financial penalties for non-compliance.

The only Asian nations with high recycling rates, owing to the tons of recycled waste, are Taiwan and South Korea. As for China, it ranks 30th on the list of the top recycling countries. Since 2021, it has banned the import of solid waste for environmental and public health reasons, and to boost its local industry.

For Pakistan, the Global Recycling League Table report labels the quality of municipal data as “very poor.” In another report by Yale University, Pakistan is ranked 113 out of 180 countries for recycling in 2022, following which specific rankings are unavailable. Despite the poor ranking and scarcity of data, recycling as a practice remains widespread in Pakistan.

Autonomous waste pickers and junk-shop dealers, better addressed as “sustainopreneurs,” form the backbone of the country’s shadow industry that processes plastic, glass, paper, and metals. The less than 390,000 tons, out of 3.9 million tons, of plastic waste that gets converted into pellets and subsequently supplied to industries, is collected and sorted by these workers.

Pakistan’s only recycling-related federal-level statute is the Hazardous Waste Management Policy (2022). According to it, the government has to collaborate with private sector stakeholders on identifying recyclable waste and offer incentives for establishing recycling programs.

Though existing recycling efforts cannot match Pakistan’s annual waste production—estimated at 50 million tons—there is sufficient evidence of the lucrativeness of recycling for the government to formalise the industry. Data from Lahore alone illustrates that household solid waste recycling generates 271 million PKR ($0.962 million) annually, even though only 21.2% of recyclable waste in the city is recycled.

Moreover, according to the Sustainable Development Policy Institute-based researcher, Zainab Naeem, providing microfinancing, technical training, and licensing to ~200 recycling SMEs could yield 1.1 billion PKR ($3.88 million) annually. The SMEs’ existing performance substantiates this projection: their limited and formally unsupported recycling has already achieved an impressive 84% plastic recovery.

The details depicting the economic viability and cost-effectiveness of such operations, if scaled, are depicted in Table 2:

Table 2: Cost-Benefit Analysis for 200 Recycling SMEs in Pakistan

Source: From Waste to Wealth

Table 2’s projections depict Pakistan’s 830 million PKR ($2.947 million) profits even if only 200 recycling SMEs are patronised. Overall, the industry, besides promoting cleanliness, resource conservation and civic attitudes, would catalyse macro-economic growth whose impact trickles down to the grassroots. However, it confronts challenges that can only be overcome by government action.

While Pakistan is the world’s fifth populous state and its solid waste is growing annually at 2.4%+, the country lacks formal recycling and composting infrastructure. Such governmental negligence leaves waste picking to the 200,000 to 333,334 untrained workers, resulting in only 13% recyclable recovery from municipal solid waste. Contrarily, formally establishing the recycling industry could save the government up to 65 million PKR ($0.229 million) annually.

Another challenge is low awareness of waste management, which is linked to recycling. Unlike Europe, where recycling originates from awareness imparted through education, Pakistan’s system does not empower citizens to play their part.

Furthermore, manufacturers are not legally bound to produce recyclable items and take them back post-consumer use. This shifts the financial burden of reprocessing to recyclers, hampering business scalability.

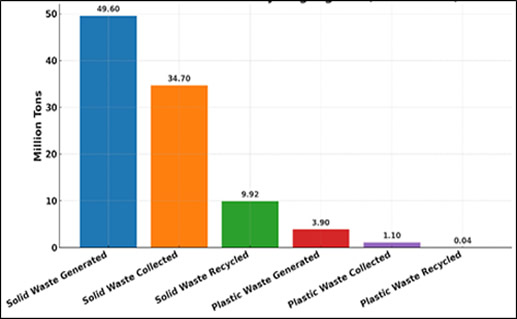

Statistics in Graph 1 show how the annual amounts of solid and plastic wastes recycled are tellingly lower than those generated and collected:

Graph 2: Pakistan’s Current Recycling Figures (Million Tons)

Source: Multiple

Merely 9.92 and 0.04 million tons of waste recycled illustrate successive governments’ underinvestment in the sector—perpetuating its informal nature and subpar performance. As described earlier, this translates into the country’s annual failure in seizing economic gains.

The government must now build the industry covering all recyclables, recognising its economic potential. Modern infrastructure should be invested in the country, whose capacity matches the daily waste generated. Leveraging informal workers’ experience, the existing industry also needs regulation and integration into this new recycling setup.

Moreover, federal and provincial administrations must prioritise awareness-raising from childhood education. Further, as scholar Zainab Naeem suggested, actively choosing products manufactured from recycled materials to reduce the consumption’s environmental impact, the government must sensitise people accordingly to boost the recycling industry.

Lastly, Pakistan needs to promulgate overarching laws mandating the recycling of all materials. As described earlier, Pakistan has a law relating to recycling; however, that is confined to the hazardous waste category.

If the above steps are initiated, Pakistan’s recycling industry would be empowered to catalyse national economic growth from the macro to micro levels.