With its three fundamental pillars of politics, policy, and administration, the governance structure relies

heavily on the bureaucracy to uphold the Weberian Principles of Impartiality and Neutrality. This is crucial for

effective governance. However, political interference often disrupts this equilibrium in many developing

countries, including Pakistan. Instead of prioritising efficient service delivery, the bureaucratic system

frequently succumbs to self-interest, undermining its core purpose.

Over the past 20 years, governance in Pakistan has seen a significant decline in effectiveness, with its ranking

dropping from 37.84 to 29.25 percentile. This decline can be attributed to factors like law and order, economic

conditions, corruption, lack of meritocracy, and, above all, the deviation from political neutrality. Despite the

government’s approximately 40 reform commissions and committees, the problem of ineffective governance persists.

On 18 September 2024, the Institute for Strategic Studies, Research and Analysis (ISSRA) at National Defence

University (NDU) organised a focused group discussion with subject matter experts, including former and serving

bureaucrats and experts from academia, media, and the legal fraternity to find root causes of bureaucratic

inefficacy and propose a pathway towards responsive governance in Pakistan.

The bureaucratic system in Pakistan has a rich historical context. This system was inherited from the British

Colonial Administration, which set up the Indian Civil Service (ICS) to ensure that the administrative leadership

remained institutionally disconnected from the masses and continued to serve the interests of the Crown alone.

Although Pakistan attempted to indigenize the bureaucratic system after its independence, the spirit of rigidity

and class structure persisted. Understanding this historical context is crucial to comprehend the current state of

the bureaucracy.

Analysis of governance reforms in Pakistan since independence shows that commitment was the hallmark of the

bureaucracy during the initial years despite resource constraints. Experts cited the 1973 constitution's dropping

of constitutional protection for bureaucracy enshrined in the 1956 and 1962 constitutions, with a special

provision of ‘show cause notice,’ protecting removal and termination of service as a gateway to political

interference in the bureaucracy. The 1973 reforms removed that provision, leaving the bureaucracy vulnerable to

political pressures.

The reforms also introduced a notorious “lateral entry” system, opening doors for political recruitments, thereby

declining the quality of recruits and general trust in the system. The literature presents lateral entry as a

consolidating agent in politicising Pakistan's bureaucracy.

Although the 1993 Civil Service Ordinance restored legal protection through the Presidential Ordinance, it proved

very short-lived and lapsed after its term completed.

Although there is general criticism of government officials being paid low salaries, a 2022 report presented that

wage premiums for civil servants might be relatively low. Still, non-monetary benefits are 13% higher than private

ones. For FY 2018- 2019, the Government’s salary expenditure cost was 242 billion rupees, while the non-salary

expenditure cost was 226 billion rupees. This shows that the perception of non-salary perks being the primary

motivation for the political patronisation of bureaucracy is incorrect.

Politicisation is also seen in postings, transfers, and promotions. The experts extensively deliberated on this

aspect and concluded that the drive to secure desirable postings, transfers, and tenure security lay the basis for

the politicisation of bureaucracy. Clause 21 of Rules of Business 1973 has set the term for regular posting at a

station as 3 years. Still, it does not materialize in many cases due to politically motivated pre-term postings.

The most infamous case of this politicisation is ‘Anita Turab versus Federation of Pakistan,’ where the Supreme

Court ruled that security of tenure must be ensured, except for compelling reasons, which should be recorded in

writing and would be subject to judicial review.

While deliberating on solutions, the experts agreed that the bureaucracy must internally develop a system to

ensure the security of tenure. A senior bureaucrat cited a relatively higher degree of political interference at

the provincial level than at the federal level, where political leaders often overstep into allotments and

intra-office matters of civil servants. Here, decentralization of power and delinking of the financial authority

of politicians and bureaucracy would be fruitful. A senior bureaucrat asserted that the financial responsibility

needs to be shifted to local bodies, ensuring direct accountability through closer proximity between the public

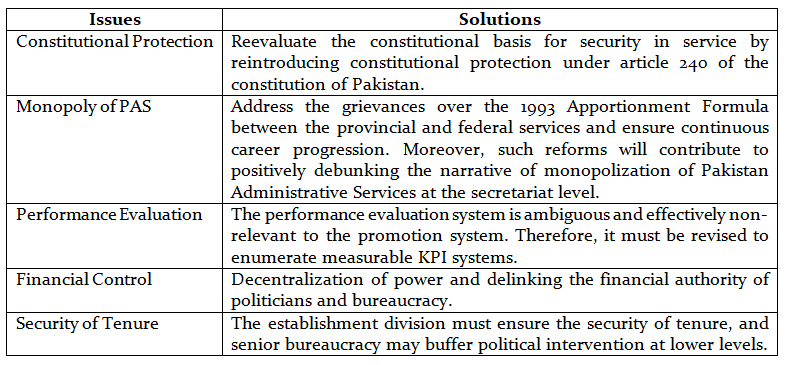

and their decision-makers. In this regard, the experts presented two-pronged strategies:

Furthermore, reports on civil service reforms reflect a disconnect between performance evaluation and promotion

systems in Pakistan’s bureaucracy. In a survey conducted on bureaucrats, 84% of respondents confirmed no link

between efficiency and better postings. The bureaucracy in Pakistan is said to operate in an ill-construed Annual

Confidential Reports (ACR) system centered on the officer's personal qualities rather than measurable targets.

This disproportionate evaluation and reward system has amplified the politicisation of bureaucracy. Therefore,

experts pressed for a KPI-based evaluation system that discourages cylindrical career growth and promotes a

pyramid progression in service, eventually reducing political influence.

In addition to those above, the experts also argued that political interference and victimization under the garb

of accountability have impaired bureaucratic efficacy. The discussion also took stock of the monopolization of

administrative service and emphasized debunking the narrative of monopoly through the resettlement of the

Apportionment Formula of 1993.

In conclusion, the solution to depoliticise bureaucracy is not new but straightforward. It is high time to tackle

the issue using a well-structured, multitiered plan that balances the three pillars of governance. Although

multiple reform efforts have been made, none have brought the intended success. Therefore, it is high time to

create a comprehensive plan for depoliticising bureaucracy, focusing on aligning principles, strategies, and tools

across all levels of governance. A concise summary of key findings is presented below.

Action Matrix

The views expressed in this Insight are of the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect the policy of ISSRA/NDU.