Pakistan has been caught in a continuous fight against terrorism for over twenty years, mainly using military-led efforts. Although significant tactical wins have been made through various military operations, these have not led to lasting peace. This analysis suggests that, due to the changing and ongoing terrorist threats and the growing pressure on military resources, Pakistan needs a dedicated National Counter Terrorism Force (NCTF).

Although Pakistan's counter-terrorism framework includes provincial Counter-Terrorism Departments (CTDs) and paramilitary forces, the reliance on the military as a primary force has caused several vulnerabilities. First, it potentially diverts the armed forces’ focus and resources away from external threats, especially in an era of shifting geopolitical dynamics. Second, operations conducted by armed forces in aid of civil power (Article 245) lack a robust, permanent legal framework. It also raises potentially serious concerns about human rights compliance in counter-terrorism (CT). Third, the Provincial CTDs are constrained by jurisdictional boundaries. At the same time, federal paramilitary forces, such as the Frontier Corps (FC) and Rangers, have mandates primarily focused on border security and law enforcement support, rather than specialised CT operations. Besides structural limitations, the military has been constantly engaged against terrorism since 2004. The CT operations intensified from 2008 to 2009.

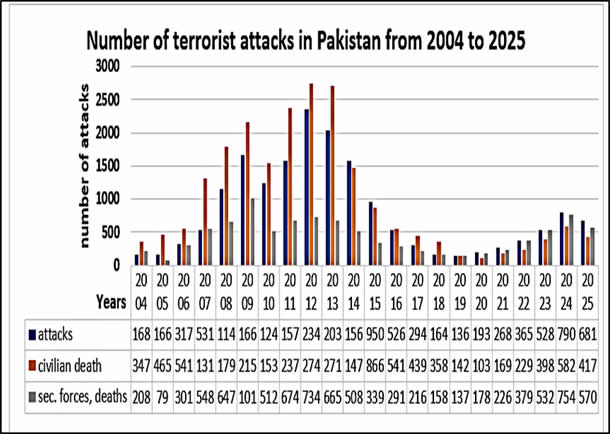

After the attack on Army Public School in Peshawar (2014), operations further increased, and Operation Zarb-e-Azab (2014), Operation Radd-ul-Fassad (2017) and other intelligence-based operations were launched. However, these operations achieved varied successes. The threat of terrorism has increased after the takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban in 2021, as shown in Graph 1. This rise in terrorism, along with the structural limitations, highlights the need for the establishment of a specialised force, NCTF, which could be the primary force against terrorism.

Graph 1:

Source: South Asia Terrorism Portal

Globally, nations facing significant internal threats have established specialised national-level forces to address terrorism without relying on the military, which Pakistan could emulate as a model.

The French Gendarmerie, a military force with police duties that operates primarily in rural areas and small towns, specialises in counter-terrorism operations. The Italian Carabinieri, which functions as both a police force and a military branch, has specialised units dedicated to counter-terrorism that can operate nationally without regional limitations.

Similarly, the Spanish Guardia Civil, a military force charged with police duties that has developed exceptional expertise in combating domestic terrorism, particularly against Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) – a far-left nationalist organisation, and jihadist groups. Another example is the United States Department of Homeland Security, which coordinates numerous agencies and resources under a unified command structure to address domestic terrorism threats. These forces demonstrate that effective CT requires a dedicated, hybrid institution with nationwide jurisdiction, clear legal authority, and capabilities that sit between those of a soldier and a police officer.

The first national internal security policy (NISP) 2014-2018 called for a Federal Rapid Response Force in collaboration with provincial CTDs. Similarly, point 8 of the National Action Plan (NAP) 2014 called for a specialised CT force, which has been omitted in the revised NAP 2021, and needs to be reconsidered.

Pakistan recently converted the Frontier Constabulary into a federal force, a positive step; however, it remains a police force primarily aimed at maintaining law and order, rather than a counter-terrorism specialist unit. Moreover, CT tasks are still primarily undertaken by the Pakistan Army and paramilitary forces.

Pakistan does not need to build an entirely new force from scratch, as it would be cost-prohibitive and time-consuming. A more practical solution is to reorganise existing resources by designating Frontier Corps and Rangers wings in all provinces, currently employed on internal security duties, into the NCTF. These forces have years of experience and intelligence in countering terrorism across Pakistan.

This force may have a federal mandate to conduct CT operations across all provinces and territories without jurisdictional limitations.

It may operate under the Ministry of Interior for day-to-day CT operations, but be placed under the Ministry of Defence in the event of war or as the situation demands.

Although the use of Article 245 and the Anti-Terrorism Act 1997, amended over time, allows the armed forces to act in aid of civil power, a new NCTF Act that grants it permanent national jurisdiction and full police powers (arrest, investigation, prosecution) for terrorism-related incidents may be necessary. This will provide clarity, enhance judicial processes, and ensure compliance with human rights. With these capabilities, it might be a hybrid force with military-level tactical expertise, unified command and police-style investigative, forensic, and community engagement skills. It may also maintain close intelligence coordination with NACTA, IB, ISI, and CTDs.

The longevity and adaptability of NCTF could be of critical importance. If the terrorist threat declines significantly, the force could be transitioned to remain a vital national asset, avoiding irrelevance. It could take on roles to tackle organised crime, cyber terrorism, civil defence, and community engagement etc. NCTF may also contribute to global CT efforts by sharing expertise with other countries. It may remain a flexible, cost-effective, and strategically relevant pillar of Pakistan’s national security architecture. It may expand or scale back its functions depending on Pakistan's security needs.

The CT strategy of Pakistan necessitates institutional strengthening rather than quick fixes or improvised deployments. Establishing NCTF might be more of a strategic imperative than merely a tactical one for Pakistan. It has the potential to address the limitations of the current military-led approach by providing a dedicated, legally robust, and nationally coordinated solution. By learning from international experiences and optimising existing resources, NCTF offers a cost-effective and practical way forward. Additionally, its design allows for adaptability to future security environments, particularly if terrorism declines, ensuring it remains a valuable asset for Pakistan. The concept of NCTF represents a proactive investment in building a more secure, stable, and resilient Pakistan.