The National Security Strategy (NSS) of the United States (US) reflects the country’s evolving global threat perceptions and strategic objectives. Since the end of the Cold War, US approach to South Asia has evolved, shaped by the Soviet disintegration and the War on Terror, to a rising rivalry with China.

This Insight traces shifts in US NSS language since 1987, highlighting key inferences that reveal South Asia’s changing role in American grand strategy.

NSS 1987 (President Reagan) had warmly praised Pakistan for “withstanding strong pressures [due to the] Soviet invasion of Afghanistan,” offering to “bolster the security of Pakistan” for aiding the “Afghan cause.”

NSS 1990 (President Bush) referred to both Pakistan and India as “friends,” expressing a desire to “encourage Indo-Pakistani rapprochement” while reaffirming a “special relationship” with “traditional ally Pakistan.”

NSS 1995 (President Clinton) urged India and Pakistan to “cap, reduce and ultimately eliminate their weapons of mass destruction and ballistic missile capabilities.” NSS 1997 reiterated the need for both to align “their nuclear and missile programmes into conformity with international standards.”

NSS 1998, reacted sharply to nuclear tests, criticising them for “contributing to a self-defeating cycle of escalation” and urging immediate accession to the CTBT. NSS 1999 and 2000 echoed similar concerns, calling to “respect the Line of Control in Kashmir” and “join the NPT” to avoid the possibility of a “dangerous arms race in South Asia.”

NSS 2002 (President George W. Bush) stated: “With Pakistan, our bilateral relations have been bolstered by Pakistan’s choice to join the war against terror.” It acknowledged India’s potential to become “one of the great democratic powers in the twenty-first century” and appreciated it for “working hard to transform” its bilateral relationship with the US.

NSS 2006 praised Pakistan’s “effective efforts” in counterterrorism while elevating India through the landmark civil nuclear deal and a “roadmap [for] meaningful cooperation.” The strategy, while addressing South and Central Asia as adjacent regions, highlighted Afghanistan’s “historical role as a land bridge” for connecting “two vital regions.”

By 2010, a broader regional framework began to take shape. NSS 2010 (President Obama) pledged to “strengthen Pakistan’s capacity to target violent extremists” while building a long-term “strategic partnership.” India was now described as “a key centre of influence” whose “responsible advancement” provided “an opportunity for increased economic, scientific, environmental, and security partnership.”

NSS 2015 placed South Asia within the new context of the US “Rebalance to Asia and the Pacific.” It called for working with both India and Pakistan to “promote strategic stability, combat terrorism, and advance regional economic integration” but aligned India’s “Act East” policy with American regional interests.

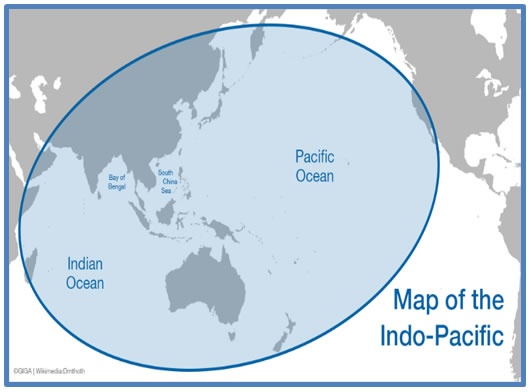

NSS 2017 (President Trump) was a turning point. The strategy replaced “Asia-Pacific” with “Indo-Pacific” and described China as a “revisionist power” seeking to “displace” the US. India emerged as a “Major Defence Partner,” while Pakistan was cautioned to demonstrate its willingness to decisively confront “terrorist groups operating on its soil” or risk losing “trade and investment ties.”

Source: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA)

The latest NSS 2022 (President Biden) declared 2022-2032 “a decisive decade” for US-China competition. It underscored the need to counter China’s so-called “coercive behaviour” and ensure a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” by deepening ties with India, which it declared “world’s largest democracy” and “Major Defence Partner.” While providing an “overview” of US “strategic approach,” this NSS highlighted alliances like “Quad,” “I2U2,” and “AUKUS” to “deepen cooperation with like-minded states. Pakistan was not mentioned for the first time since NSS 1993.

An overview of US NSS since the end of the Cold War reveals that the pendulum of US priorities in South Asia shifted from a focus on both countries to one on India. While the 1990s NSS mainly adopted a neutral tone, post-9/11 strategies narrowed Pakistan’s significance to counterterrorism efforts in Afghanistan.

Over time, Pakistan’s status declined from a “special relationship” (1990) to a complete omission (2022). Conversely, India’s standing steadily rose from a “friend” (1990) to a “regional security provider” (2015) and “Major Defence Partner” (2022), indicating Washington’s shift in favour of New Delhi. Pakistan, which was once a key ally in countering Soviet influence during the Cold War, was no longer perceived as a suitable partner for the US in achieving its strategic objectives in South Asia.

The shift in US policy was driven by its changing geopolitical lens. As China replaced the USSR as its primary adversary, the US began to view India as a counterweight to China and a potential “net security provider” in China’s surrounding region. However, India reaps the benefits of its defence and security ties with the US-led West and Russia, as well as its economic partnership with China. Although this strategy reduces its overdependence on any single power, the support of big powers gives India a false sense of strength. Posing a risk to regional stability, this strategic over-smartness leads India to assertive actions, such as its recent conflict with Pakistan in May 2025. If Western support for India goes unchecked, volatility in the region may escalate, compounded by India's internal issues, such as Hindutva-driven democratic backsliding, innumerable freedom movements, and societal polarisation.

Amidst the shifting trajectory of US security strategy and its deepening alignment with India, Pakistan cannot afford to only react to the geopolitical landscape. With a clear and resilient foreign policy, Pakistan needs to reinforce ties with China (CPEC, cybersecurity, AI, green technology, etc.) and diversify partnerships, especially with middle powers and Global South forums. Relevance in regional stability, counterterrorism, and connectivity, especially vis-à-vis Afghanistan, Central Asia and the Gulf, is also essential for Pakistan. To reclaim its strategic visibility in Washington, considering its post-Marka-e-Haq improvement in relations with the US, Pakistan must increase engagement through think tanks and diaspora. This will also restore balance in South Asia’s strategic equation by countering India-centric framings, i.e., narratives that prioritise India’s perspective while sidelining other regional voices, especially Pakistan.

The views expressed in this Insight are of the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect the policy of ISSRA/NDU.