The World Bank defines the blue economy as a “sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and jobs while preserving the health of the ocean ecosystem”. The shipping sector serves as the backbone of the blue economy, as over 80% of global trade is carried by sea. This insight analyses the impact of Pakistan’s shipping sector on its maritime trade performance.

Pakistan’s 95% trade and 100% of its oil and coal imports rely on sea transport. However, the annual revenue from Pakistan’s blue economy is only US$1 billion, or around 0.4% of the national GDP (significantly below the global average of 7%), against its estimated potential exceeding $100 billion. Ships serve as mobile storage units, enhancing the country’s overall storage capacity and lessening reliance on foreign carriers.

The Pakistan National Shipping Corporation (PNSC) is the only national flag carrier. It falls under the administrative control of the Ministry of Maritime Affairs (MOMA) as an autonomous body. PNSC currently operates 10 vessels with a total capacity of 724,643 metric tons deadweight tonnage (DWT) for dry and liquid bulk cargo. It is listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange and primarily funds its operations through internal revenue.

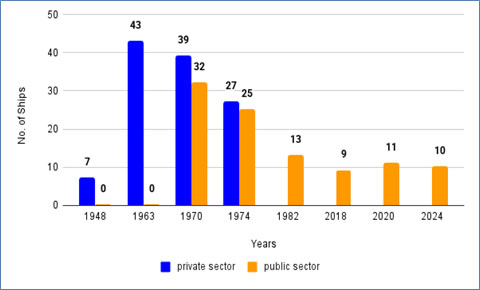

In the 1970s, the National Shipping Corporation (NSC) operated 71 ships, which were primarily owned by the private sector (Figure 1). The industry faced a setback in 1974 when 26 ships from nine operators were nationalised to form the Pakistan Shipping Corporation (PSC).

In 1979, NSC and PSC were merged to form PNSC, the country’s sole state-owned shipping entity. PNSC’s fleet peaked with 60 ships in the 1980s but declined to 16 by the 1990s due to retirements, lack of new acquisitions, and limited private registrations. Contrary to popular belief, PNSC’s current fleet of 10 vessels carries about 724,643 DWT, more than its 1979 fleet of 48 ships, which had a total capacity of 579,486 DWT.

Figure 1: Ships owned by Public and Private Sectors Since 1947

Source: Self-compiled

Pakistan’s total merchandise trade (imports and exports) stood at $85.45 billion in 2024. However, PNSC manages only 11% of Pakistan's cargo by volume and 4% by value. With over 90% of its trade transported by foreign shippers, Pakistan faces a significant foreign exchange drain of around $4–5 billion in freight payments, which negatively impacts its foreign reserves.

Furthermore, in the past five years, global geopolitical tensions have disrupted key international shipping routes. The disruptions in the Suez Canal caused over 2,000 ships, including those bound for Pakistan, to be rerouted via the Cape of Good Hope in late 2023. This led to an additional 10 days and $1 million in fuel and insurance per vessel, causing freight costs to double or even triple.

Moreover, in the aftermath of Pakistan-India military escalation of 2025, India’s restriction on cargo originating from or destined for Pakistan compelled shipping lines to offload such cargo before docking at Indian ports. As a result, several shipping lines suspended Karachi calls, with an estimated weekly disruption of 6,000 to 7,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) in export volume from Karachi.

Thus, there is a pressing need to build a sustainable and competitive national fleet that strengthens Pakistan’s economic potential and national security.

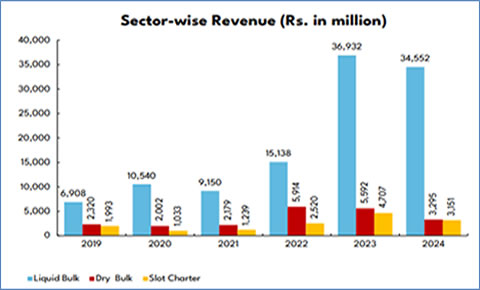

The PNSC fleet operates in liquid and dry bulk only. Despite the higher national dry bulk trade (67.17 million tons) compared to liquid bulk (29.20 million tons) in 2024, PNSC’s share in liquid cargo stood at 32%, while its share in dry bulk remained just 2%. This gap stems from PNSC’s dry bulk vessels, which fall short of international standards in terms of deadweight capacity. For instance, PNSC’s Supramax vessels carry approximately 52,951 tons, which is below the global average of 58,328 tons. Figure 2 shows that liquid bulk consistently dominates PNSC’s revenue, with a steep rise from Rs. 6,908 million in 2019 to Rs. 36,932 million in 2023. In contrast, dry bulk and slot charter revenues remain relatively modest. Additionally, PNSC currently does not operate any container vessels to facilitate general cargo trade.

Figure 2: Revenue Share

Source: PNSC

Another key obstacle to the growth of Pakistan’s shipping sector is the lack of investment from the private sector. Pakistani private shipowners collectively own eight ships, all of which are registered under the Flags of Convenience (FoC) countries and not PNSC. These shipowners attribute their reluctance to invest under the national flag to inconsistent government policies, bureaucratic red tape, and extensive paperwork. Pakistan’s low ranking (108th out of 190) on the Ease of Doing Business index further reinforces this hesitation.

To increase participation, a very liberal Merchant Marine Policy (MMP) was introduced in 2001; however, full benefits remain unrealised due to gaps in policy implementation. Despite having a highly liberal and tax-friendly maritime policy on paper compared to regional peers, Pakistan’s shipping sector remains underdeveloped (Table 1).

The MMP lacks the binding legal authority of an act or ordinance. Its provisions are dependent on periodic decisions by the cabinet and the Economic Coordination Committee (ECC). For instance, the exemptions from customs duty, income tax, and sales tax on ship imports provided under the MMP expired in 2020 and were not renewed thereafter. Moreover, in the Fourth Amendment Finance Bill (2021), the government imposed a 17% sales tax on vessel acquisition, and has begun taxing seafarers’ salaries. While these fiscal steps may help address revenue needs and broaden the tax base, they come at the cost of undermining a strategic industry.

Table 1: Regional Comparison of Maritime Policies

Source: Self-compiled

In contrast, India, Bangladesh, and Iran have stable policies and tend to achieve more sustained fleet growth and global integration, even without heavy tax incentives. Similarly, Turkey’s fee exemptions and Vietnam’s capped costs attract more tonnage, while Pakistan’s lack of fiscal incentives and sea blindness hinders private sector growth and fleet expansion.

Now, PNSC is implementing an ambitious plan to expand its fleet from 12 to 34 vessels by 2028, aiming to generate $700 million in freight earnings over the next three years. In parallel, the National Logistics Corporation (NLC) has launched Pakistan’s first containerised flagship shipping service to Gulf countries.

Complementing these initiatives, Pakistan is set to build its first major commercial cargo ship in 40 years, a $24.75 million containership project revived through the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC), reflecting renewed momentum in domestic shipbuilding.

These are good initiatives and need to be scaled up. The MMP (2001) must be upgraded into a binding legislative framework and extended for at least 30 years. Similarly, establishing a one-window operation for licensing, financing, and regulatory approvals similar to the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) will further streamline the process and boost investor confidence.