The Americas, long regarded as the geopolitical backyard of the United States (US), have witnessed an increasing shift over the past two decades. While the US remains dominant, China’s rapid economic expansion into Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) has redefined regional dynamics.

This Insight argues that, traditionally, the US has operated in the strategic backyards of its rivals. However, it faces a global competitor challenging its sphere of influence for the first time—an inversion of the “Monroe Doctrine’s” core principle, which declared the Western Hemisphere off-limits to foreign intervention.

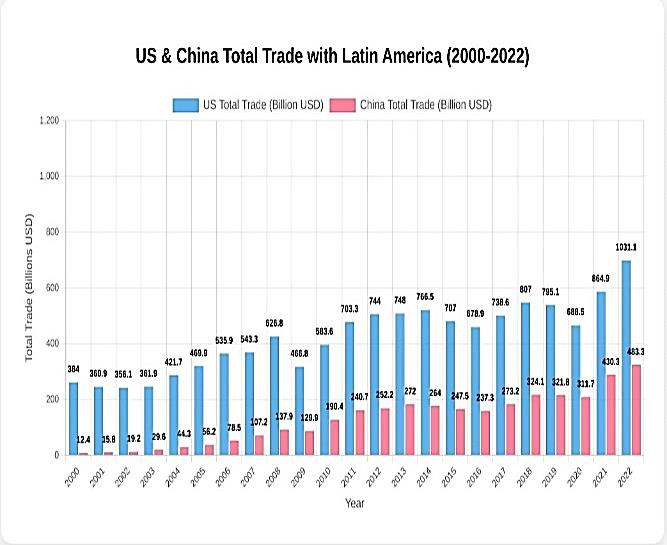

China has steadily expanded its regional economic footprint since its 2016 Policy White Paper on Latin America. From 2000 to 2022, trade surged from $12.4 billion to $483.3 billion—a 39-fold increase—compared to the US rise from $384 billion to $1.03 trillion.

While US trade volume remains higher, China’s growth has been more consistent, signalling Latin America’s shift toward diversified partnerships.

Trade Volume of the US and China with Latin America (2000-2022)

Source: Council on Foreign Relations

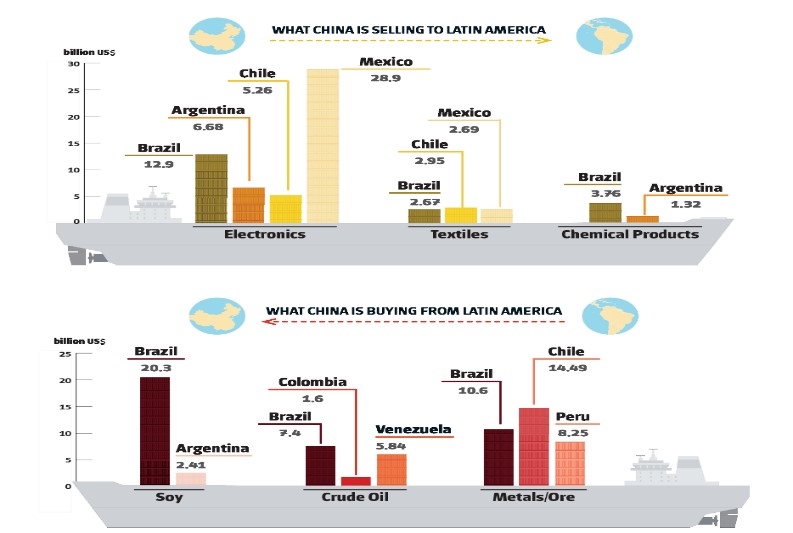

China is now the top trading partner for countries like Brazil, Chile, and Peru. Latin American exports of raw materials, agricultural goods, and imports of Chinese-manufactured products mark this relationship.

Moreover, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has funded ports, railways, and energy projects across the Americas, boosting infrastructure but sparking concerns over debt dependency and declining US influence.

Chinese Exports and Imports to Latin America

Source: Americas Quarterly

Through investments, China facilitates its trade with the region and gains a strategic foothold that could have long-term implications for US dominance in the Western Hemisphere. For example, the Chancay Port, a deep-water project near Lima, Peru, initiated in 2019 by China’s COSCO Shipping Ports, with the first phase of construction starting in 2021, is designed to become a key hub for Asia-South America trade, reducing reliance on US-controlled routes.

In 2022, China’s COFCO secured a 25-year concession to develop a terminal at Brazil’s Port of Santos, boosting access to agricultural and mineral exports. Similarly, Costa Rica’s Moín Terminal, inaugurated in 2019, has become a key entry point for Chinese goods into Central America, marking strategic inroads into a US-dominated region.

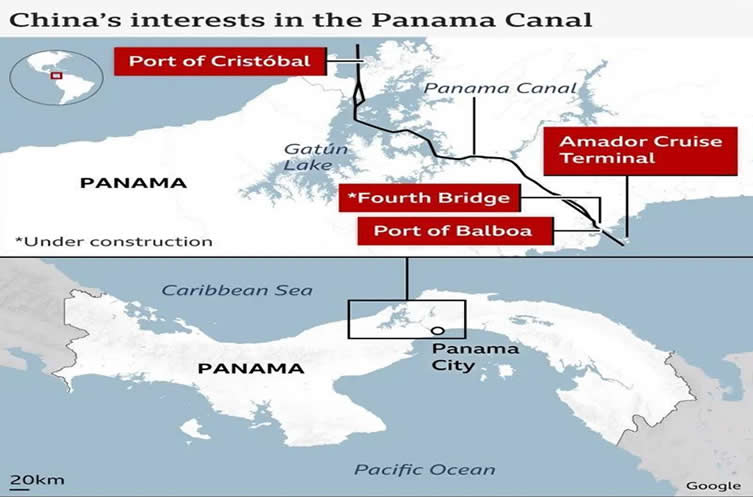

The Panama Canal is one of the most critical chokepoints in global trade, accounting for approximately 5% of global container trade passing through it annually. Around 72% of transiting ships are going to or coming from US ports. China’s Landbridge Group holds a 25-year concession to operate Panama’s Port of Colón, a key global trade hub. The deal boosts China’s control over a vital supply chain node and its influence over canal-linked maritime traffic.

China’s Infrastructural Projects in LAC

Source: Inter-American Dialogue

President Trump’s push to reclaim the Panama Canal cited concerns over alleged Chinese control. In a notable shift, Panama’s President Mulino announced in February 2025 that the country had withdrawn from the BRI.

China has signed comprehensive strategic partnerships with key LAC countries, including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela, and concluded around 1,000 bilateral agreements to boost trade, investment, and cooperation across diverse sectors.

By 2022, China had established 45 Confucius Institutes in South America, including 11 in Brazil and others across Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Venezuela. Meanwhile, a growing Chinese diaspora and business presence are rising in regional economies.

Between 2013 and 2024, President Xi visited Latin America six times—more than Presidents Obama, Trump, and Biden combined. In 2023 alone, eight Latin American presidents made official visits to China, a record high.

China’s economic and diplomatic incentives also serve as leverage to promote its "One China" policy. It now has formal relations with all regional states except Paraguay and a few Caribbean nations that recognise Taiwan.

Source: BBC, Panama Ports Company, China's government reports

While limited compared to its economic ties, China’s defence cooperation in the Americas is growing. Between 2009 and 2019, it supplied $634 million in military hardware—aircraft, vehicles, and small arms—to Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela. China has also provided training and equipment to police forces in Bolivia and Venezuela and conducted joint military exercises with Brazil and Chile. Though limited compared to US engagement, these steps reflect China’s growing geostrategic interest in the region.

Hence, China’s growing presence against what was once safeguarded by the US Monroe Doctrine is more than a shift in influence—it marks a profound geopolitical reversal. For over a century, the US acted freely in the strategic peripheries of its competitors. Today, it faces a global rival applying similar tactics in its hemisphere. Unlike past challengers, China has advanced not through military confrontation but through trade, investment, and diplomatic engagement, embedding itself deeply in the region’s economic and political fabric.

Historically, external powers such as the Soviet Union and earlier European colonial actors sought to project influence in Latin America, often through ideological alignment or proxy movements—as seen in Cuba, Nicaragua, Chile, and Grenada. These incursions were met with swift and forceful US responses, including covert operations, sanctions, and regime changes.

The 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis and 1983 Operation Urgent Fury in Grenada stand as stark examples of Washington enforcing its claimed strategic domain. However, where others were repelled, China succeeded—its method is based not on ideology or arms but on ports, infrastructure, and pragmatic diplomacy.

This reversal is especially striking given the history of the US intervening in the backyards of rival powers. From backing the Afghan Mujahideen during the Soviet occupation to supporting opposition movements across Russia’s near-abroad and reinforcing military alliances around China, the US has not hesitated to apply pressure in others’ spheres.

Washington, now treating China’s economic engagement in the Americas as a strategic threat, suggests anxiety over shifting influence and a recognition that Beijing’s non-military, long-term approach may be more effective than traditional power projection. Notably, the US response to China has relied on a “Strategy of Disruption,” seeking to slow or block Chinese initiatives rather than offering compelling alternatives. Such a defensive posture, focused on containment rather than competition, may have short-term utility but lacks sustainability. Undoubtedly, a strategy centred on disruption makes it hard to succeed against a rival that is building rather than breaking, connecting rather than confronting.

Unless Washington replaces its strategy of disruption with competitive, constructive initiatives, it risks falling behind a rival that is steadily shaping the region’s future through connectivity, investment, and diplomacy.

The views expressed in this Insight are of the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect the policy of ISSRA/NDU.