Pakistan, one of the largest and fastest-growing digital markets with about 116 million internet users (the 10th largest in the world), includes 71 million who actively engage with major social media networks (SMNs). Despite an extensive digital footprint and huge potential, none of these SMNs maintains a local physical presence in terms of offices. This paradox of high user engagement and limited corporate presence raises key questions about digital sovereignty, regulatory effectiveness, and national security. This insight examines why global SMNs avoid physical presence, explores successful localisation strategies from comparable markets, and suggests practical ways for Pakistan to encourage these companies to establish local offices.

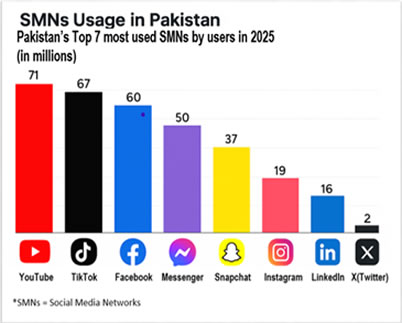

Pakistan’s digital landscape is rapidly expanding with widespread use of major global SMNs, which underscores its status as a vibrant consumer market, as illustrated in Graph 1 below. This strengthens the case for global tech giants to establish local offices in Pakistan.

Currently, global SMNs such as YouTube, Twitter (X), Instagram, TikTok, and Facebook (Meta) serve millions of Pakistani users without any physical office or registered legal entity. They operate remotely in Pakistan through regional hubs in Singapore, Dubai, or India, managing Pakistani content, advertisements, and regulatory matters from abroad.

Graph 1

Source: Compiled by Author

Instead of direct local engagement, they rely on online support systems, digital tools, liaison representatives, or third-party partners to interact with Pakistani authorities, creators, and advertisers. Regulatory correspondence, such as requests for content removal or legal notices, is processed through online portals or regional legal teams, resulting in delays or incomplete responses.

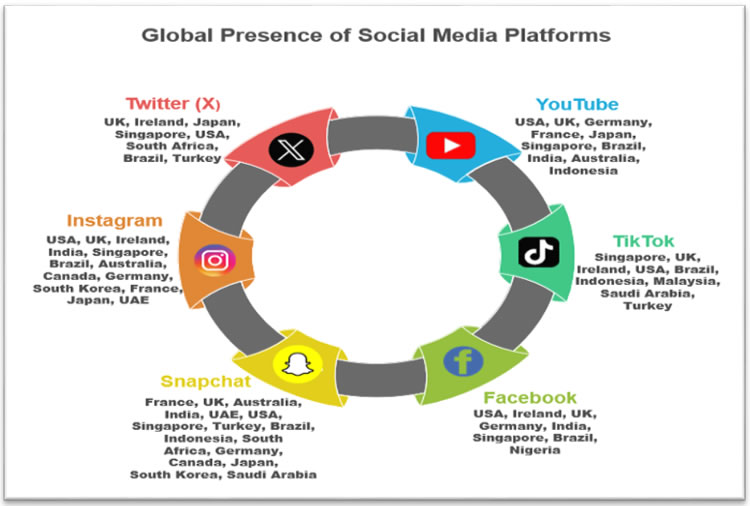

Overall, these SMNs generated approximately PKR 7 billion (~USD 25 million) in revenues from Pakistani users, with only PKR 785 million collected as tax revenue in 2024. A local office could integrate these earnings into Pakistan’s economy (through corporate taxes, local salaries, and services). Chart 1 below illustrates the global locations of Central SMN's Offices.

Chart 1

Source: Illustrated by Author

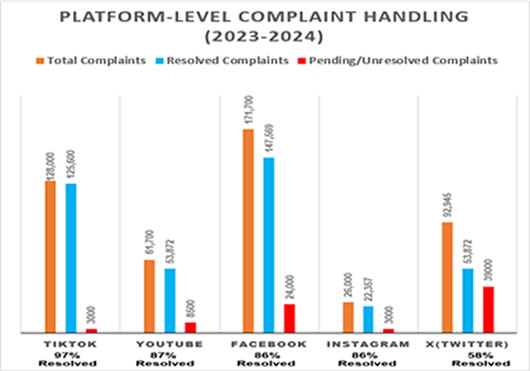

The lack of local offices results in poor content moderation, as remote teams often lack cultural awareness—consequently, Pakistan resorts to disruptive measures like nationwide bans, which negatively impact millions of users. Graph 2 below shows the status of complaints processed by these major SMNs. As of 2024, TikTok had the highest content removal rate (98% resolved), while X (Twitter) was the worst performer (only 58% of complaints resolved).

SMNs are hesitant to localise themselves in Pakistan due to several key reasons, including regulatory uncertainties, operational risks, modest economic incentives, political volatility, uncertain government policies, lack of data protection laws, and security threats against local representatives. All of these concerns encourage SMNs to continue remote operations.

Graph 2

Source: Compiled by Author

SMNs harvest vast Pakistani user data, including location, behaviour, communications, political views, and biometrics, creating national-security risks (manipulation, surveillance, hybrid warfare, democratic erosion). Many states mandate or pressure data localisation: Russia and China enforce strict local storage, while Vietnam and Indonesia require local servers/registration. Turkey, Nigeria, and Saudi Arabia apply conditional controls. Currently, no fully enforced, comprehensive law mandating data localisation in Pakistan for these SMNs. Without local offices or data-protection laws, Pakistan lacks oversight. Pakistan should enact a robust Personal Data Protection law, requiring sectoral localisation for sensitive/state-critical data, mandating security assessments for cross-border transfers, and incentivising the development of local data centres.

Local offices would improve regulatory compliance by enabling the direct enforcement of local laws, such as the PECA Act 2016 and the Citizen Protection Rules 2020, enhancing content moderation, and reducing nationwide disruptive bans. Furthermore, local offices would boost the country’s economy through increased corporate tax revenue and the creation of high-skilled jobs, providing more employment opportunities as these SMNs would fall under the oversight of agencies such as the SECP and FBR.

Content moderation would become more effective through direct coordination with regulators, such as the National Cyber Crime Investigation Agency (NCCIA) and the PTA, ensuring culturally sensitive and timely responses to harmful content, thereby improving the user experience and reducing societal tensions. In summary, the localisation of SMNs would strengthen Pakistan’s digital sovereignty, allowing for better governance and management of its data within its borders.

Countries like Brazil and Nigeria have adopted a stricter approach towards localisation. For instance, in 2024, Brazil’s Supreme Court upheld the ban on X (Twitter) and fined $1 billion because the platform refused to provide local representation and content moderation. Similarly, Nigeria banned X in 2021 for seven months due to non-compliance with regulations. In these cases, the ban was only lifted once the platform agreed to establish local offices, and this enforcement motivated other major social media networks to comply and localise as well.

This illustrates how strict or conditional regulations and market access requirements can drive localisation.

On the other hand, Saudi Arabia achieved localisation through a collaborative approach toward SMNs, emphasising partnerships and financially incentivising localisation . In contrast, Turkey adopted an incremental pressure tactic, requiring SMNs to localise or face increasingly strict penalties, such as advertising bans and bandwidth throttling. Though initially hesitant, most SMNs complied by establishing local representation. These two countries demonstrated the successful implementation of more moderate and cautious approaches to localisation.

Pakistan actively seeks to localise SMNs through regulatory and diplomatic initiatives. Prominent efforts, such as the Citizen Protection (Against Online Harm) Rules 2020, required these SMNs to establish local offices, appoint representatives, and implement data localisation. However, fallout from international and domestic digital groups led the government to soften its approach in subsequent revisions. By 2023, authorities allowed virtual offices and online representation without a mandatory physical setup and localised data. Additionally, the removal of the unlawful Online Content Rules 2023 streamlined content regulation by categorising prohibited material and setting compliance timelines. Pakistan also engaged with SMNs diplomatically through consultations, such as those in the Asia Internet Coalition.

Despite many efforts and significant digital potential, Pakistan has not succeeded in bringing these SMNs home and faces major setbacks due to their remote operations. Pakistan must strategically enhance its regulatory framework, implement strong data protection laws, incentivise SMNs to localise by offering tax rebates, simplified registration, and access to subsidised tech zones, while encouraging partnerships with local firms and talent. Gradual localisation mandates, coupled with government advertising commitments and high-level diplomatic engagement, can make establishing local offices both financially attractive and strategically beneficial.