This insight reviews Pakistan’s current technology policymaking. It emphasizes the strong connection between technology policymaking and our modern national security and economic interests. It also associates the success of new policy initiatives with national political unity and ownership.

In 2016, the World Economic Forum (WEF) identified social platforms as essential contemporary tools for shaping political narratives. The Social and Technology platforms (STPs) are multifaceted, financially robust, and technologically advanced global non-state actors, such as Google, Huawei, Meta, Microsoft, Temu, TikTok, and WhatsApp. They collect cis and trans frontier social, commercial, and personal data and are quintessential partners for states in their digital, economic, and social transformation agendas.

Over the past decade, the world has witnessed numerous instances of deliberate manipulation of perceptions and the weaponisation of citizens’ beliefs and emotions through social platforms, causing disruptions in statecraft and social behaviours, such as general elections and civil unrest. Another concern is the increasingly questionable role of STPs in recent interstate conflicts, e.g., the Russia-Ukraine War and the Israel-Palestine conflict.

In 2022, the US State Department established the Bureau of Cybersecurity and Digital Policy, signalling the significance of technology policymaking in the future of US diplomacy. In addition, political alliances such as BRICS and the EU are creating their playbooks for working with STPs to safeguard economic and security interests.

For the Global South, one of the most profound political challenges arising from the rise of social platforms is the increasing contestation between various actors and the state over its hegemony in ideological and domestic political narratives. This contention has transformed the national digital eco-chambers into battlegrounds mediated by STP’s community guidelines, i.e., Digital No-Go Areas for the state, lacking national legal oversight or regulatory control, and proprietary algorithms driven by commercial motivations, often leading to governance and social challenges.

Furthermore, the role of STPs as data accumulators without national oversight presents a governance and legal challenge. The US restrictions on TikTok and Huawei, as well as Chinese restrictions on Meta and Google, respectively, represent this threat. In this context, the Internet firewall is a national right with a data protection regime as a national priority. However, they alone are insufficient to address the spectrum of issues at hand.

The origins of Pakistan's version of the Post Truth Era (PTE) can be traced back to 2013, with Ma’arka-e-Haq (Op Bunyan Ul Marsoos) being a watershed of the third (latest) phase. Historically, it has been driven by domestic political agendas, a policy context that continues to influence the mindset of decision-makers. The country’s engagement with social platforms is publicly well-documented. It is kinetic and one-dimensional, focusing on enforcement, such as PECA 2016 and subsequent amendments, blocking platforms, and crackdowns. It is thus not surprising that our internet and content governance reporting is an annual count of enforcement activities, as evident in the different reports of the PTA.

On the other hand, our relationship with technology players is a continued policy and legal enigma. For example, Meta and Google are the top two commercial players in Pakistan's media market, with a reported market share of over one-fifth, totalling PKR 25.78 billion out of PKR 114 billion in 2024. This is a mere US$90 million at current currency conversion rates. The double irony here is that they are not registered with the media and telecom regulators, and our state and commercial sectors do not see eye-to-eye on the market share of these two players.

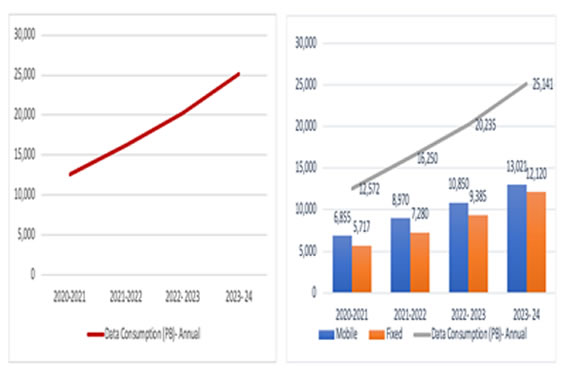

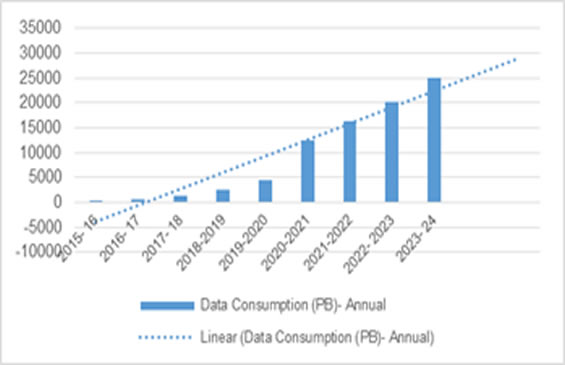

While these figures may be underreported, expecting these two larger entities to open offices in Islamabad, even to double the reported revenues, is commercially irrational. However, for them, the Pakistani market is a valuable data source with 150 million broadband users, which produced 25 thousand Petabytes (PB) of data in 2024 and has experienced a nearly 20% CAGR (Fig 1) in 2021- 2024, and around 60% CAGR 2016- 2024 (Fig 2) periods, respectively. Furthermore, WhatsApp is an interesting case that lacks national oversight but is widely used by both decision-makers and the public alike. It has only recently been banned by the US House of Representatives due to concerns over the opacity of its data handling protocols.

Figure 1: Data Consumption in Pakistan FY 21- FY 24

Source: PTA Reports

Pakistan needs to integrate STPs into a comprehensive policy framework. The modern digital society is a dynamic interaction among the State, Society, and the STPs. The following five key policy vectors guide this relationship:

Figure 2: Data Consumption in Pakistan FY 16- FY 24

Source: PTA Reports

Pakistan needs to rethink its technology policymaking and its domestic digital data as integral components of its national security. The state, as the principal orchestrator of this transformation via opportunity creation, enabling, facilitating, and lastly enforcing the lifecycle, requires a single ownership and steering structure to implement these vectors and other policy structures. Such a structure should be ideally located within the Prime Minister’s office at the National Security Division (NSD).