The shifting contours of the international system have brought new opportunities and challenges for states once locked in historical rivalry. Pakistan and Russia spent the better part of the Cold War on opposing sides, now find themselves moving closer in a rapidly transforming world order. Their relations are no longer framed by divergences; rather shaped by convergences in geopolitics, security, and regional stability.

While defence, diplomacy, culture, and people-to-people contact-including academic exchanges and limited tourism form important elements of the relationship between Pakistan and Russia; but given the centrality of trade and connectivity in interstate relations, this Insight focuses on the economic dimension of the relations between two countries.

The synergies and untapped economic potential between Pakistan and Russia are significant. Pakistan’s consumer market of over 240 million is projected to be the world’s sixth largest by 2030 (PPP terms). On the other hand, Russia as a $2.02 trillion economy with reserves above $580bn—offers Pakistan a sizeable market, alongside a diversified industrial base, civilian nuclear knowledge and vocational expertise. Moreover, a study by Pakistan Business Council estimated Pakistan’s unrealised export potential in Russia at about $2.8bn.

Pakistan’s energy demand grows by over 8% annually, aligning well with Russia’s strengths as the second-largest natural gas exporter and third-largest oil producer. Pakistan also imports over $1.5 billion of wheat and edible oils annually, where Russia holds about 20% and 14% of global market share. For both sides, cooperation in these domains is important for diversification: Pakistan secures alternate sources for energy and food supplies, while Russia broadens its export markets beyond traditional buyers.

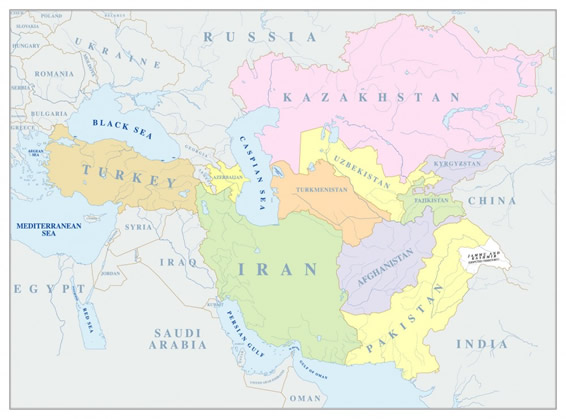

Geography adds another layer of synergy. Pakistan’s strategic location offers Russia overland access to the Indian Ocean via Gwadar and Karachi Ports, and can connect Moscow to the world. In return, Russia, via its Caspian–Volga–Don links and Black Sea/Baltic gateways, offers Pakistan a structured access to European markets avoiding conflict ridden chokepoints in sea.

In the geopolitical domain, Afghanistan, once a source of discord, now forms the bedrock of their converging interests. Russia remains deeply concerned about terrorism and drugs spilling into Central Asia and onwards. In a pragmatic yet strategic move, Russia became the first country to formally recognise the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, signaling motivations for "regional stability, economic gains, and the desire to reshape the international order". On the other hand, Pakistan seeks a stable western neighbor to manage its own internal security challenges, while also aiming to unlock transit corridors like CASA-1000 and TAPI.

These overlapping interests have facilitated cautious intelligence exchanges, diplomatic consultations, and modest defense cooperation—including the annual Druzhba military exercises since 2016, and joint naval drills such as Arabian Monsoon.

What sets Pakistan-Russia relations apart in today’s world order is the absence of divergences. Unlike Pakistan’s ties with the US, faced by periodic strains, Islamabad’s convergence with Moscow is free of conflicting interests.

However, the bilateral trade data (presented in the graph) between Pakistan and Russia between 2014-2023 proves that trade between the two has underperformed relative to the strategic rhetoric surrounding the relationship. Though it almost doubled from $542 million in 2014 to $1.04 billion in 2023, growth has been modest, and the current figures fall well short of the relationship’s potential.

Source: State Bank of Pakistan (SBP): Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS): Trade Development Authority of Pakistan (TDAP): UN Comtrade Database; Russian Federal Customs Service (FCS): World Bank and IMF Trade Summaries.

In 2023, the bilateral trade made up just 1.2% of Pakistan’s and 0.23% of Russia’s total trade. This means that in trade terms, Pakistan is a marginal partner for Russia, while Russia, though more important to Pakistan than before, still lags behind major partners like China, the US, and the EU.

For Pakistan, present trade is import-driven with the balance favoring Russia. Pakistan mainly exports textiles, sports goods, medical instruments, and fruits to Russia, while it imports grains, crude oil, coal, and pulses.

The limited economic gains reflect structural inadequacies rather than intent on both sides. Pakistan remains tied to Western-linked finance—20+ IMF arrangements since 1958, with multilaterals holding about one-third of external public debt. So, maintaining IMF access, rollovers and USD clearing is critical. Moreover, the Western countries account for over 50% of Pakistan's export market, reinforcing this dependence. Deepening economic relations with a sanctioned Russia therefore risks this relationship. On Moscow’s side, trade with China ($240bn), and India ($65bn), dwarfs the $1bn with Pakistan, so Islamabad does not yet register as a priority market. Where economic ties have struggled, regional diplomacy shows more promise. Both countries converge on integrating Pakistan into Eurasian connectivity projects.

Source: https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/en/analyses/the-eurasian-economic-union-ambitions/

Russia has expressed interest in linking Pakistan with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), while Islamabad views access to Central Asia through Russian-backed frameworks as a way to diversify markets.

Along with EAEU, the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) with its focus on economic integration could provide the missing commercial depth to the relationship. For Pakistan, ECO provides a platform to connect its markets with Central Asia and beyond; for Russia, it offers an avenue to engage with Pakistan and other ECO countries.

Source: https://eco.int/member-states/

To unlock the potential of this relationship, both sides must address structural barriers. First, institutionalize economic cooperation by embedding bilateral trade into regional frameworks. This means actively pursuing formal trade agreements that connect EAEU with ECO, positioning Pakistan as a bridge between South Asia, Central Asia, and West Asia.

Second, prioritize establishing direct banking channels between Pakistani and Russian banks. In this context, to reduce exposure to SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) related sanctions risk and preserving continuity of settlements, Russia’s SPFS (System for Transfer of Financial Messages) can be used as the primary channel for trade-payment messaging in RUB/PKR (and RUB/CNY where relevant); while China’s CIPS (Cross-Border Interbank Payment System) can serve as a contingency path when SPFS connectivity is unavailable.

Third, advancing energy cooperation is critical. In this context, finalizing the Pakistan Stream Gas Pipeline, in an earlier timeframe is essential to establish confidence in future projects.

Lastly, Pakistan needs to embrace its western neighborhood—not just politically, but economically—by facilitating trade with West Asia, Central Asia, and Russia. This includes investment in transit infrastructure, customs modernization, and a banking framework resilient to sanctions. In essence, convergence with Russia on strategic issues is valuable, but without a robust, diversified, and institutionalized economic relationship grounded in transit trade, the partnership will remain symbolic rather than transformative.