Pakistan and Afghanistan maintain one of South Asia’s most significant bilateral trade relationships, yet the absence of a comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (FTA) continues to constrain their economic partnership. Since 2003, Pakistan has concluded 15 FTAs with various countries, whereas its trade with Afghanistan remains confined to the limited scope of the Afghanistan-Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement (APTTA). The recent Preferential Trade Agreement (PTA) signed in July, 2025, between the two countries is also limited to eight agricultural products only, leaving all other sectors aside. The difference between a PTA and an FTA is that the former provides preferential tariff rates for a limited number of items, while the latter aims to eliminate most tariffs on goods.

This insight examines the merits of an FTA, reasons for its delay, associated challenges, and the way forward. Trade between Pakistan and Afghanistan is currently facilitated under the APTTA signed in 2010, replacing the 1965 Afghanistan Transit Trade Agreement (ATTA). APTTA was intended to provide Afghanistan with access to sea routes through Pakistani ports. Additionally, both countries are members of the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA), which came into force in 2006. However, SAFTA has limited influence due to Afghanistan's late accession in 2011 and the broader geopolitical tensions in South Asia.

While APTTA theoretically promotes transit cooperation, in practice, its implementation has faced severe challenges.

Pakistan has expressed concerns over smuggling and misuse of transit goods while Afghanistan accuses Pakistan of creating unnecessary bureaucratic hurdles. The frequent closure of key crossings like Torkham and Chaman has further disrupted supply chains and exacerbated political tensions.

The bilateral trade between Pakistan and Afghanistan has demonstrated both resilience and volatility, with Pakistan's exports to Afghanistan reaching $1.24 billion in 2024. It shows a 7.55% annual growth over five years. Despite this growth, the relationship faces structural challenges, including security concerns, infrastructure deficits, and the absence of a comprehensive trade framework that could unlock the full economic potential between these neighboring states.

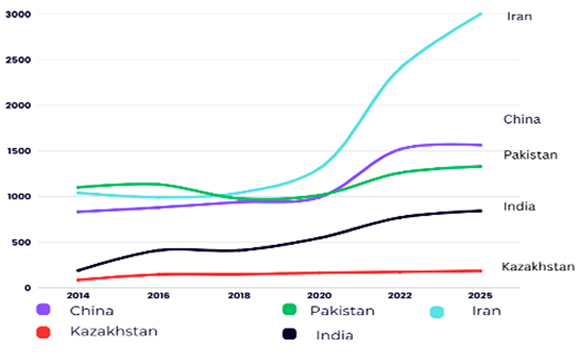

Afghanistan’s trade relations have witnessed a structural shift over the last decade. Iran has surged ahead as the leading partner, while China has also expanded its footprint significantly as shown below in figure 1. Both countries now outpace Pakistan, which, despite geographic advantages, shows only moderate growth and declining relative share.

Figure 1: Afghanistan’s Imports with Leading Trade Partners (2014–2024) in Million Dollars

Source: Self Extracted

India has gradually increased its role, though it remains behind the top three partners. Kazakhstan’s share has stayed small but steady. Overall, the trajectory signals a reorientation of Afghan trade toward Iran and China, with Pakistan facing growing competition.

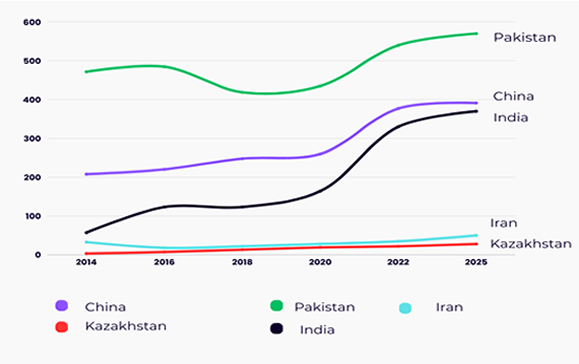

Figure 2: Afghanistan’s Exports with Leading Trade Partners (2014–2024) in Million Dollars

Source: Self Extracted

The trends in figure 2 show that Afghan exports remain heavily oriented toward Pakistan, which continues to dominate as the primary destination. China and India have emerged as growing markets, with sharp increases after 2020, reflecting diversification in Afghanistan’s export base. By contrast, Iran and Kazakhstan account for only marginal shares in exports. Overall, though Pakistan is the biggest importer of Afghan products but recorded $900 million trade surplus with Afghanistan in 2024.

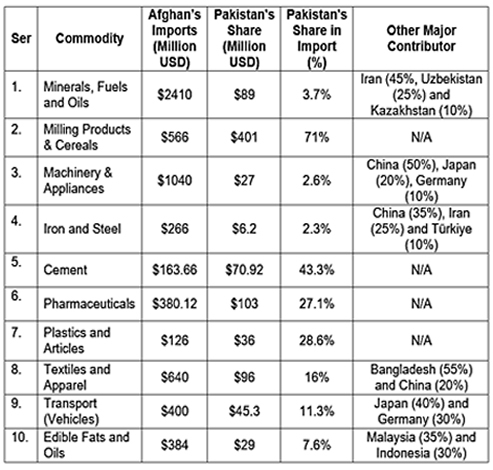

Pakistan already dominates several essential export categories, including food items, vegetables, cement, and household articles as given below in table 1. This dependency underscores Pakistan’s leverage in trade negotiations. Out of $8.5 billion, the below given table covers $6.3 billion of Afghan imports. Pakistan only makes $903 million in these categories despite domination in several areas.

Table 1: Afghan Imports from Pakistan and Their Share in Total Percentage in Imports in 2024

Source: Self Extracted

Current bilateral trade stands at $1.7 billion. Pakistan already supplies key Afghan imports, including cereals (71%), cement (43.3%), and pharmaceuticals (27.1%), yet captures only $903 million of $6.3 billion in major sectors, highlighting vast untapped potentials.

This gap between Pakistan’s current export share and Afghanistan’s overall import demand needs a comprehensive FTA to unlock the full trade potential, as Pakistan has surplus in milling products, cement, and textiles. It can also expand several industrial areas. The economic rationale for a Pakistan-Afghanistan FTA is strengthened by Afghanistan’s landlocked geography. This creates natural economic interdependence and gives Pakistani exporters a substantial advantage through lower transportation costs. Beyond staples, Pakistan has ample room to grow in higher-value sectors. An FTA could further enhance exports in transport, electronics, IT and professional services.

It will also help curb smuggling and bring the informal economy into the formal sector. As a result, the current bilateral trade can be expanded to an estimated $5 billion.

Although Afghanistan has not yet signed FTA with any other country, it has PTA with Iran and Uzbekistan. Afghan-Iran agreement focuses on technical services, pharmaceuticals, food products, and petrochemicals. Similarly, an initial phase of PTA was signed with Uzbekistan also.

In July, 2025, Pakistan signed Early Harvest Programme (EHP) or PTA to reduce tariffs on eight products, which each country was producing in surplus. Afghanistan will export grapes, pomegranates, apples and tomatoes, and Pakistan will export mangoes, orange, bananas and potatoes on a preferential basis under the framework of this agreement. These products have limited economic value as they represent only 10% of the total bilateral trade. But the potential lies in medicine, cement, cosmetics, and other industrial sector.

In conclusion, a Pak-Afghan FTA would strongly favor Pakistan which can expand existing trade surplus. Since Afghanistan has no FTA with any country, Pakistan can be the first to secure preferential access. Previously, Pak-Afghan trade talks failed in 2015, over Kabul’s demand for access to India, but there has been no such demand at the signing of recent PTA. Pakistan can leverage its existing PTA to pursue a comprehensive FTA by either gradually expanding the list of goods already covered or by moving directly to a full-scale FTA.