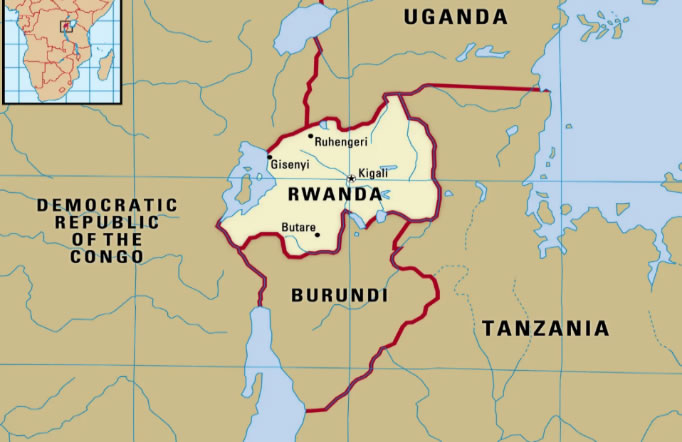

Rwanda’s journey is among Africa’s most remarkable recoveries. This Insight assesses Rwanda’s post-genocide recovery and its rise as a regional linchpin and mineral hub. Rwanda, known as the Land of a Thousand Hills, lies in the heart of Central Africa. Covering just 26,338 km², it is a small, landlocked nation bordered by Uganda to the north, Tanzania to the east, Burundi to the south, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to the west.

Figure 1: Geographical Map of Rwanda

Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica

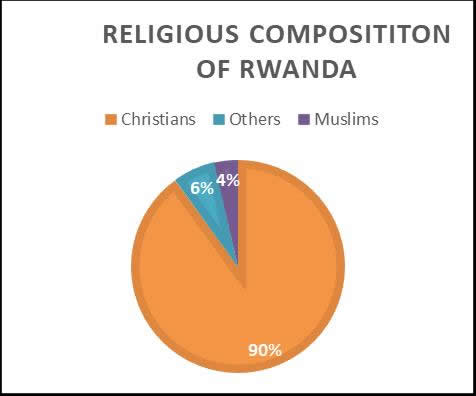

Figure 2: Religious Composition of Rwanda

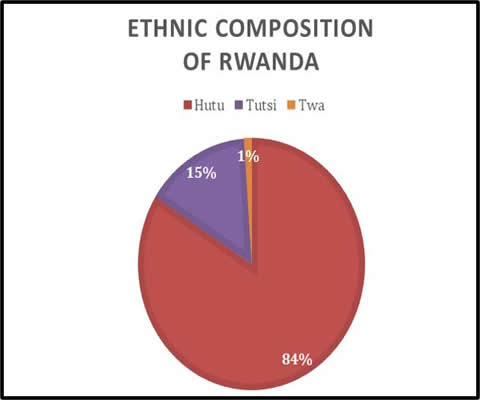

Figure 3: Ethnic Composition of Rwanda

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the country’s current religious and ethnic composition.

Rwanda’s history is shaped by complex ethnic dynamics, colonial legacies, and political upheaval. For centuries, the Kingdom of Rwanda operated as a centralised monarchy under Tutsi kings, encompassing Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa communities. This balance shifted after German colonisation in 1899 and later Belgian rule following World War I. Belgian policies deepened ethnic divides by favouring the Tutsi minority and institutionalizing hierarchies that fuelled long term resentment.

Independence in 1962 reversed this balance, with the Hutu majority taking power. Tutsis faced systemic discrimination, driving many into exile, where they formed the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) in 1987. The Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) launched its armed struggle in 1990 to challenge decades of ethnic discrimination and political exclusion under the Hutu-dominated regimes, particularly that of President Juvénal Habyarimana. Tensions peaked on 6 April 1994 when Habyarimana’s plane was shot down, triggering a 100-day genocide in which extremist Hutu militias, backed by elements of the Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR), killed around 800,000 people - mainly Tutsis and moderate Hutus - while the world stood by. The civil war ended with the RPF’s military victory under Paul Kagame.

In the aftermath, Rwanda confronted the immense task of rebuilding a traumatised society. The transitional government led by Kagame (1994-2003) prioritised unity and reconciliation through state-driven governance and centralised control, focusing on restoring security and rebuilding political and economic institutions. International guilt -particularly in the US and the West - for failing to prevent the genocide, combined with strategic concerns over renewed conflict and regional spill over, generated intense moral and political pressure to back Rwanda’s post-genocide rebuilding process.

The UN supported the recovery through Resolution 955 (1994), which established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda to prosecute those responsible for the genocide, helping restore UN credibility and stabilise the Great Lakes region, along with humanitarian relief. By 1997, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) had launched governance, judicial, and socio-economic reforms to rebuild the nation.

In 2003, Rwanda adopted a new constitution that created the framework for an elected government under President Paul Kagame. It provided a basis for political legitimacy and reform-oriented governance within a democratic framework.

International partners - including the United Nations (UN), United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO - formerly DFID), and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) supported Rwanda with technical aid and financial assistance for governance, rights, and electoral processes. The US assisted through the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), which has supported HIV reduction, diagnostics, and universal health coverage since 2002.

Simultaneously, driven by its desire for access to African markets, trade links and resources through strategic influence and soft power, China also supported Rwanda’s reconstruction. China’s investment in Rwanda began modestly in the early 2000s (US$2-5 million) but reached about US$62 million (3.7%) by 2017. By 2024, its share reached 14.1% (US$460 million), driven by growing involvement in Rwanda’s infrastructure and energy sectors.

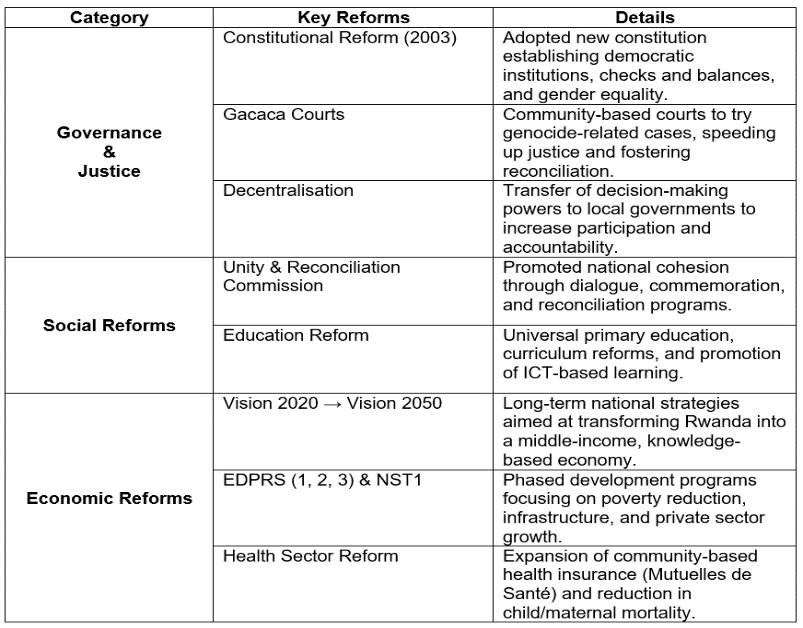

Rwanda’s reform trajectory has since progressed in structured phases. Some of the significant reforms are summarised below.

Figure 4: Key Reforms Post-Genocide

Source: Self-Compiled

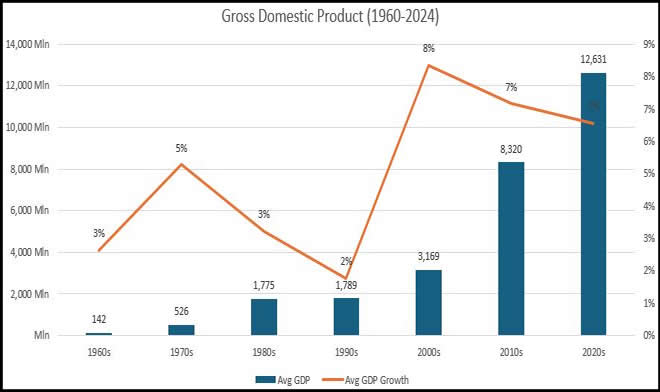

Moving forward, Rwanda rebounded economically, aided by foreign donors such as the World Bank (WB), International Monetary Fund (IMF) and through investment in healthcare, infrastructure and Education. Since 2000, GDP has averaged 8% annual growth, stabilising at 8.2% in 2022-2023, driven by industry, services, and public investment.

Figure 5: GDP Growth of Rwanda

Source: World Bank

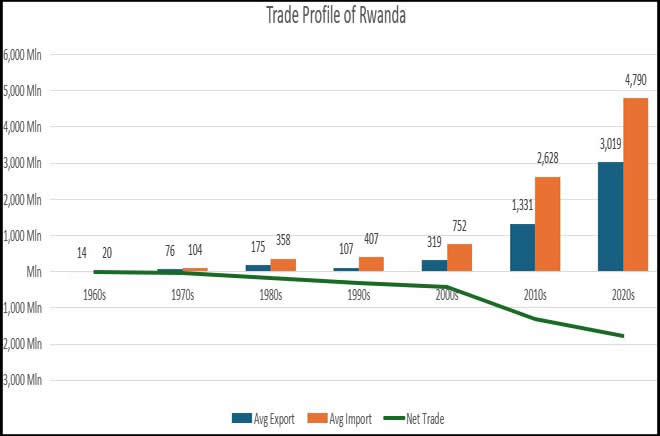

Since the 2000s, Rwanda’s trade has grown rapidly, but imports of consumer goods, machinery, and equipment continue to outpace exports, creating a persistent deficit. Exports remain concentrated in tea, coffee, and minerals. Agriculture is still the main source of employment. Yet, diversification into construction, ICT, and financial services is gaining momentum, with Rwanda positioning itself as a financial technology (fintech) hub through e-government and cashless initiatives.

Figure 6: Trade Profile of Rwanda

Source: World Bank

Kigali boosts its global visibility by hosting major events like the World Economic Forum Africa (2016), the Basketball Africa League (2021), and the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meetings (2022). Kigali hosted over 17,000 international delegates in 2024, generating an estimated $84.8 million in Mining, Investments, Conferences and Events (MICE) sector revenue.

Capitalising on its geographic location, Rwanda has rebranded itself as “Africa’s Singapore.” Backed by US and Western support for stability and reform, Kagame has consolidated power despite criticism over political repression - earning him the label of the West’s “favourite autocrat.” Washington has institutionalised its partnership with Rwanda through the 2022 Status of Forces Agreement and the 2025 US-brokered DRC - Rwanda Peace Deal, highlighting Kigali’s role as a regional stabiliser. The deal aligns with US aims to curb regional instability, secure access to critical minerals, counter China’s influence, and strengthen its diplomatic foothold in Africa. USAID committed US$85 million to local projects.

China, by contrast, engages through economic statecraft: financing infrastructure, energy, and ICT projects while leveraging Rwanda’s re-export role to maintain indirect access to Congolese minerals. Projects such as the Nyabarongo II hydropower plant, industrial parks, and integration into the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) reflect Beijing’s strategy of debt-funded development framed as “win-win” cooperation.

China has singlehandedly outweighed the US and other Western countries combined in its investments in Rwanda (Figure 7). Figures suggest that Beijing has invested US$1.2 billion since 2019 in infrastructure, manufacturing, real estate, and mining. The US$50 million cement plant in Muhanga Industrial Park alone is projected to produce one million tonnes of cement annually and create more than 1,000 jobs.

Figure 7: Rwandas Economic and Diplomatic Engagements with the US and China

Source: Self-Compiled

Rwanda occupies a strategic role in US-China competition due to its positioning as a gateway to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), home to the world’s richest cobalt and coltan reserves. Its geography has made Kigali a natural transit and re-export hub for minerals such as coltan, tin, tungsten, and tantalum, while investments in certification facilities allow it to channel “conflict-free” resources into global supply chains. This role aligns with U.S. efforts under the 2022 Mineral Security Partnership to secure responsible mineral supply chains and reduce dependence on China, which dominates global processing.

Figure 8: Critical Minerals in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Source: BBC

It can therefore be concluded that Rwanda’s trajectory to regional prominence reflects the strategic foresight of its government, which was able to successfully translate the country’s geographical leverage to domestic, political, and economic gains. Being a mineral transit hub and security broker, it has become central to US-China competition in Africa. By balancing Western partnerships with Chinese financing, Kigali wields influence that far exceeds its size, making it a pivotal hinge in the Great Lakes and the wider global resource landscape.