The events of September 2001, commonly known as 9/11, not only shook the United States (US) but also moulded a new geopolitical narrative worldwide that would shape the next two decades. Though terrorism as an element existed pre-9/11, this one single incident became the epicentre toward which the entire world constructed a tale of Islamic extremism as the principal global peril. The phenomenon was more of a domino effect, spreading from the Middle East to Northern Africa and Central Asia to Southeast Asia.

This insight highlights the spread of terrorism throughout the Muslim world post-9/11. It argues that the bogey of terrorism that spread from Africa to Southeast Asia was created primarily post-9/11. It also discusses the debate surrounding terrorism as a geopolitical tool to leverage gains.

The US-led West has well played the narrative of so-called Islamic terrorism since 2000 in securing its interests in the post-Cold War order. By identifying a monolithic enemy in terrorism, it created a convenient bogeyman through which it justified military interventions, regime changes, and resource extraction while maintaining global hegemony. Though terrorism is wrongfully linked to Islam and Muslims, the irony is not lost in the fact that the majority of the victims of these terrorist groups are Muslims. These groups preach a self-interpreted version of religion, which, in reality, is far from the actual teachings of Islam.

The statistics show that since 9/11, the majority of attacks took place in Muslim majority countries. In contrast, the West witnessed only a few and sporadic occurrences, such as the London Bombing (2005), the Paris Attacks (2015) and a few more. When somebody with Muslin ethnicity perpetrates some violent act, it is immediately labelled as ‘terrorism’, implying ideological intent. At the same time, similar acts by other perpetrators such as mass shootings in the West are framed as actions of ‘mentally ill’ individuals. The dichotomy in how acts of violence are labelled based on the perpetrator’s background highlights biases and prejudices at the global level.

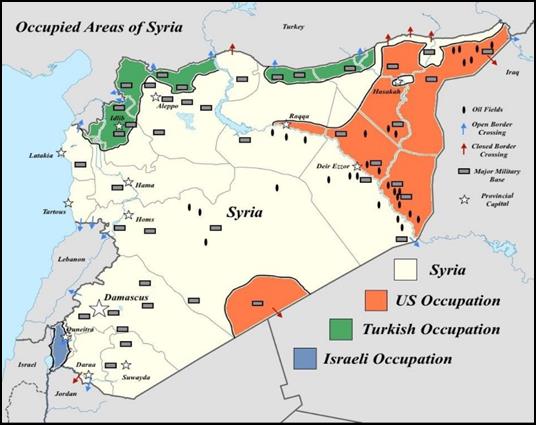

Moreover, the recent developments in Syria (figure 1) expose the role of global powers in backing local militias and terrorist organisations to secure control over land and natural resources. This pattern reflects a broader strategy where the West has exploited terrorism narrative to justify military expansion in strategic regions, including the Middle East, Central Asia, Africa, and Southeast Asia.

Figure 1: Map of Syria

Source-Reddit: (Oilfields and Military Bases)

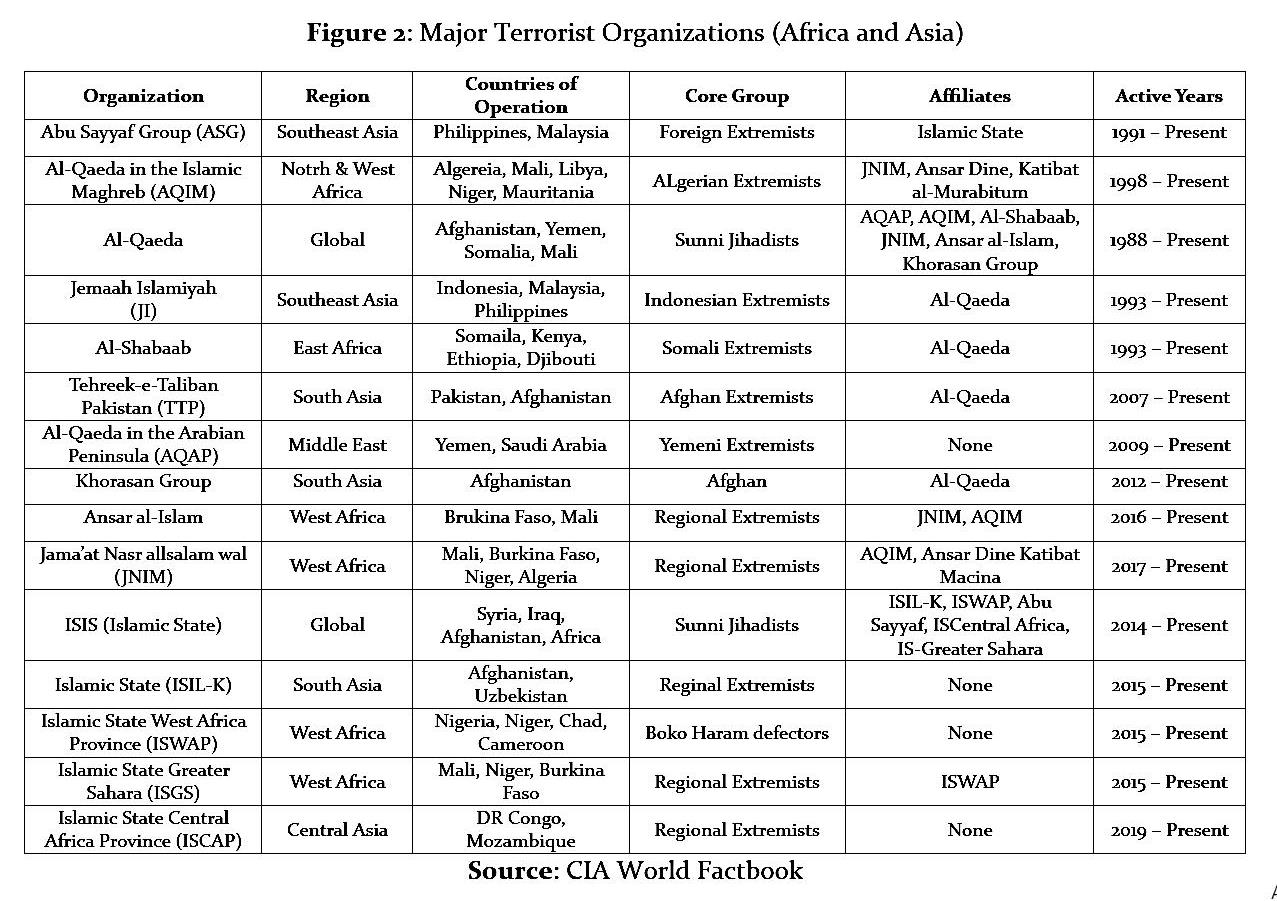

Afghanistan, for example, became not just a battleground against the Taliban but also a key site for American geopolitical influence. NATO’s involvement in operations like ‘Enduring Freedom’ demonstrated the West’s ability to unite under the banner of counterterrorism while pursuing strategic objectives. Likewise, the establishment of military bases in Iraq, Syria, and the Gulf States illustrates how the terrorism narrative has sustained prolonged Western military presence, reinforcing their dominance over resource-rich territories. The major terrorist organisations are given in Figure 2.

The so-called spread of terrorism has been hugely lucrative for the Western powers. Defence contractors such as Lockheed Martin, Boeing, and Raytheon have secured billions in profits from arms sales and military operations conducted under the pretext of fighting terrorism. According to a report by the Costs of War Project (2021), the US spent over US$8 trillion on its post-9/11 wars, much of which flowed to private defence firms and contractors. Arms sales to Middle Eastern allies also sharply rose under the pretext of fighting terrorism. Saudi Arabia alone took 12% of global arms imports from 2014 through 2018, mainly supplied by the US. It would be simplistic to deny the linkage of the arms industry to the West's foreign policy. It has benefitted and still benefits from longstanding conflicts and instability.

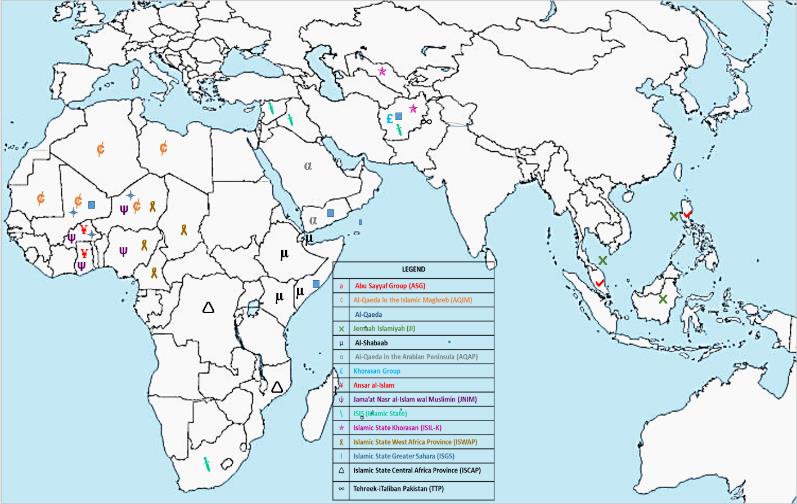

The invasion of resource-rich countries like Iraq and Libya facilitated the extraction of oil and other minerals. In Iraq, US oil companies secured lucrative contracts following the toppling of Saddam Hussein, while Libya's vast oil reserves became a focal point after the NATO-led intervention in 2011. These interventions were not merely about combating terrorism but securing access to strategic resources, reinforcing the economic underpinnings of the War on Terror. The map below shows the presence of these organisations across Africa and Asia.

Figure 3: Spread of Terrorist Organisations across Africa and Asia

Source: Self-Compiled

The Islamic world is deeply fragmented on sectarian, ethnic, and ideological lines. Hence it is prone to external manipulation. The West has effectively exploited these fissures to pursue their geopolitical interests. For instance, the 2003 US invasion of Iraq did away with Saddam Hussein's regime, which was tenuously maintaining a balance between the Sunni and Shia population. This created a power vacuum into which extremist organisations like ISIS moved to capitalise on the resultant chaos.

The case of Libya after NATO's intervention in 2011 is another example. Under the pretext of humanitarian intervention, Muammar Gaddafi's regime was toppled, and what came afterwards was a fractured state overrun by militias and extremist factions. Oil infrastructure in Libya has then been targeted and exploited, indicating very strongly the economic incentives of such Western interventions. President Trump's recent statement regarding the United States Agency for International

Development (USAID) and its funding of terrorist networks raises questions about the US commitment to combating terrorism and implies a form of indirect support. A notable example of this concern is Anwar al-Awlaki, who received education funded by USAID before joining Al-Qaeda.

The War on Terror is less about combating extremism and more about maintaining Western dominance in a rapidly changing global order. As terrorism recedes from US national security priorities, its legacy remains a stark reminder of how global narratives can be manipulated to serve powerful interests at the expense of vulnerable population.

The US National Security Strategy (NSS) from 2001 to 2008 featured terrorism as its dominant theme. However, the Biden administration’s 2022 USNSS shows great power competition with China and Russia as the main threat. This reflects a very real fact of life: terrorism, while rightly still a concern, has largely outlived its utility as a unifying narrative in the early years of the 21st century for interventions by the West.

In the aftermath, with 20 years of hindsight, one can conclude that the so-called label of Islamic terrorism, as it has arisen, is, to a great extent, a construct serving the strategic interests of Western powers. It would not be inaccurate to say that these so-called Islamic terrorist organisations have, at times, operated as US-led Western proxies. The narrative was created to dismantle the Muslim world and solidify the Western influence in different regions. These faultlines in the Islamic world conferred several economic and geopolitical benefits to many global powers and their allies in the form of arms sales, expansion of the military-industrial complex, and access to key resources, thus assisting them to retain their global hegemony.

The views expressed in this Insight are of the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect the policy of ISSRA/NDU.